Iraia Arabaolaza is an osteoarchaeologist at GUARD Archaeology Ltd, whose primary research interests are human pathologies and in particular childhood pathologies. Iraia is one of the principal co-authors for the A75 Dunragit Bypass post-excavation works and is this month’s guest contributor to the blog.

I have always believed that the study of human remains provides a direct link to our prehistoric ancestors. As archaeologists we generally rely on features (pits, structures, post-holes) and artefacts to try and reconstruct a history of how people lived in the past. The study of human remains offers an insight into a person’s biological sex, age, possible diseases that they suffered during their lifetime and even in some rare cases the cause of their death. It also provides an opportunity to better understand their belief system and associated burial rituals.

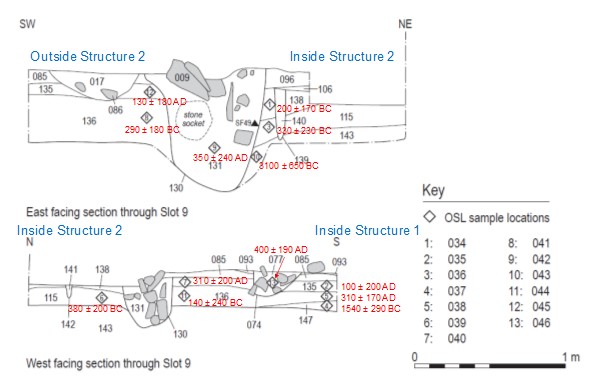

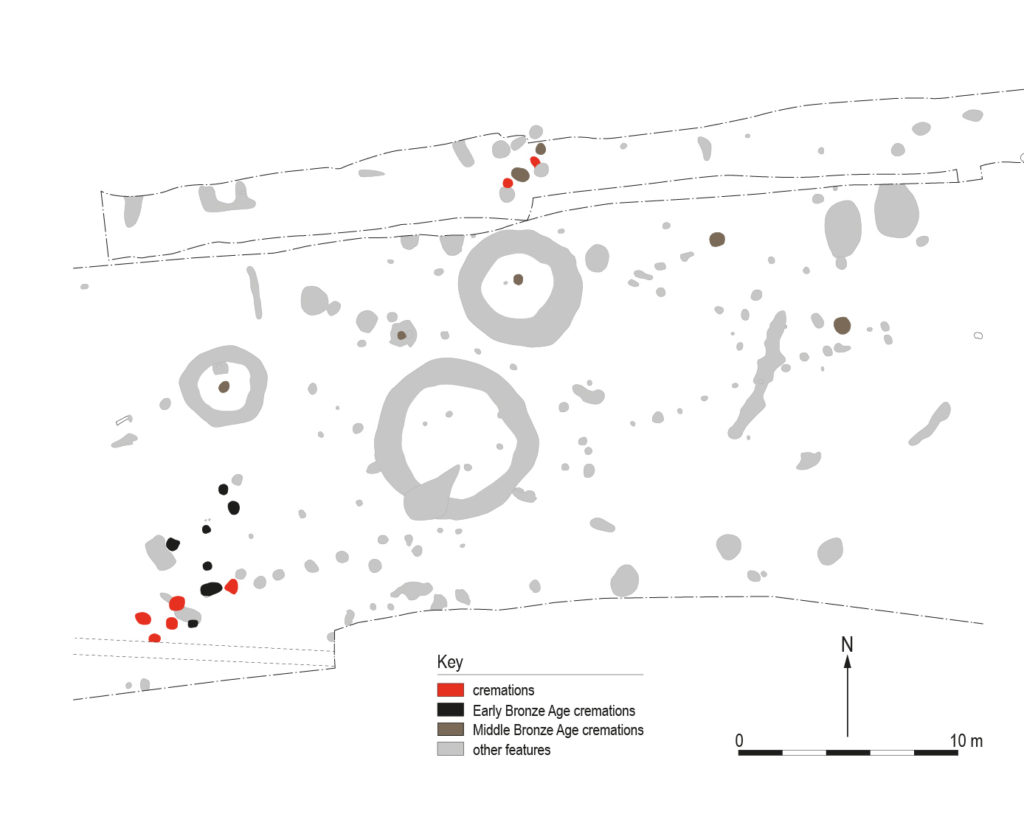

All the human remains recovered and studied from Dunragit were cremated and came from two sites, mainly Boreland Cottage Upper (27 cremations) with further three cremation remains from the Drumflower site. The cremations were either placed in urns (the minority) or in pits as a cremation deposit (the majority). No remains of pyres were encountered in the excavated areas; however, charcoal remains recovered from the cremation deposits indicated that it was mainly oak and alder that were used during the cremation rite. The earliest cremations dated to the Early Bronze Age (approximately 2000 BC) and were cremated using oak charcoal while the Middle Bronze Age cremations (approximately 1500 BC) used alder and other species including oak as fuel for their pyre.

The cremated remains were fully calcified, as they were white in colour, which indicates that the bones were subjected to a high temperature between 645 -<940ºC. The surface texture of the bones, cracks and warping suggests that most bodies were not de-fleshed prior to burning, and that the bodies were burnt soon after death. A skull fragment recovered from an urn cremation showed green/blue staining which might indicate that the bone was in contact with a grave good with copper content. However, no grave goods were found within this particular cremation, apart from the urn that contained the remains, which indicates that the metal item was not deposited within the cremation burial.

Most of the earlier cremation burials were small in weight and rather fragmented. This together with the lack or under representation of certain skeletal elements (i.e. shoulder, pelvis, rib cavity) suggests that most of the remains were possibly deposited as tokens in pits and were not representing a complete burial. Analysis based on the relative size of the bones indicated that most of the cremation deposits included the remains of at least one adult person. At Boreland Cottage Upper there was a clear change in the burial rite from a more clustered distribution in the earlier Bronze Age to more evenly distributed depositions concentrated around three ring ditches during the Middle Bronze Age. Moreover, multiple collective cremation burials were identified during this period. One urn cremation revealed two adults, one of them aged between 40-44 years and remains of a female while sub-adults or individuals younger than 18 years old were also identified buried together with an adult in three other burials. This is quite common in prehistory and could suggest they were cremated and deposited at the same time.

Several pathological conditions were noted in some of the human remains recovered from Dunragit. The pathologies included an unidentified healed infection/trauma and small bony growth, osteoarthritis on the spine and a possible sharp trauma/dismembering cut mark. Schmorls nodes, also known as intervertebral disc herniation, was also apparent – this is a lesion that appears in the vertebral body but usually causes no symptoms. Most of these are relatively easy to diagnose even on small fragments of archaeological bone and are common within the archaeological record. However, the cause of the possible infection/healed trauma remains unknown as its causes can be varied and are difficult to interpret without assessing the full skeleton. The possible cut marked bone is slightly more unusual although not unheard of from archaeological assemblages. The discovery of the cremation cemetery complex at Dunragit is of national significance. The quantity of cremations encountered in Dunragit (30), as well as the extensive use of the site for over 500 years has provided a rare insight into the Bronze Age burial practice in southwest Scotland. Although burial rites during the Bronze Age are characterised by their variety, there was clear distinction between the Early and Middle Bronze Age cremations found across the Dunragit site. While the earlier cremations were token symbolic depositions in pits, some of them with associated grave goods, the latter cremations were by and large the full remains, were associated with the ring ditch structures and were often contained in urns. Variations between these two populations in terms of their use of, and mobility within, the landscape were also apparent from the stable isotopes analysis on the cremations, but that will be another blog, while another forthcoming blog will cover the grave goods associated with these burial rites….