Alison Sheridan is a Research Associate at National Museums Scotland, whose primary research interests are Neolithic and Bronze Age Scotland. Alison is one of the specialist authors for the A75 Dunragit Bypass post-excavation works and is this month’s guest contributor to the blog.

Arguably the most spectacular artefactual finds from the Dunragit excavations are two jet spacer-plate necklaces and a spacer-plate bracelet that came from two Early Bronze Age graves at East Challoch Farm. In this blog, I’ll try to explain how we got from this:

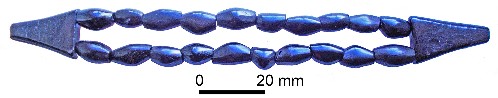

…to this:

and from this:

…to this:

…and this:

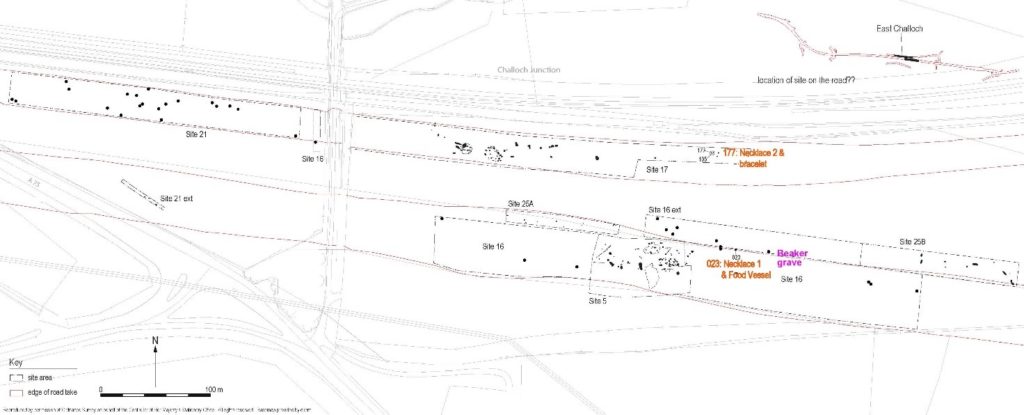

But first, the context: near East Challoch Farm, the GUARD Archaeology excavation team found several graves, including a grave with a Low-Carinated, All Over Cord Beaker, dating to 2500‒2336 BC (from hazel charcoal) – one of the earliest such graves in Scotland. The graves containing the jet jewellery are around 90 metres apart. While no meaningful radiocarbon dates could be obtained from them, we can say – from comparative dating of jet spacer-plate necklaces and from Food Vessels – that these graves most probably date to between 2150 BC and 2000 BC.

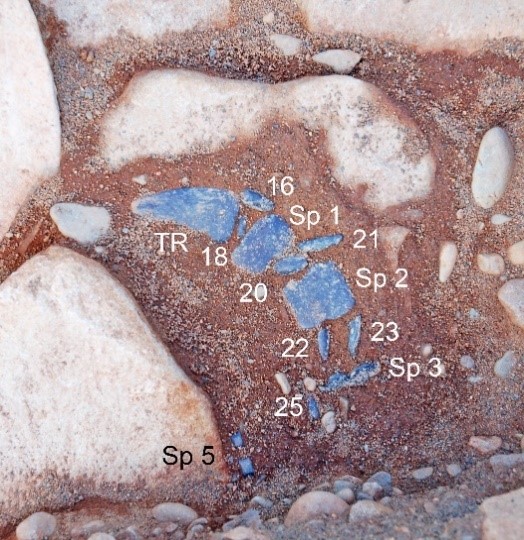

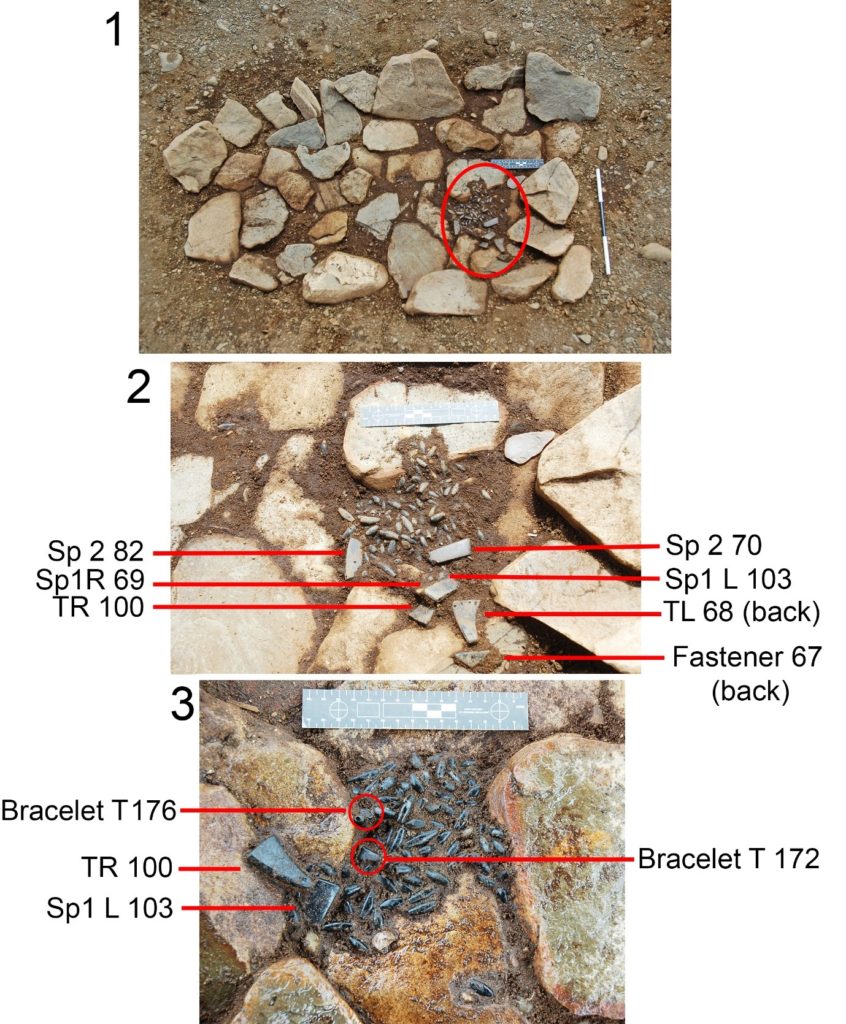

Jet Necklace 1: Grave 023 came to light when the side of a Food Vessel was revealed, at the south-east end of what turned out to be an oval, stone-lined grave orientated roughly NW/SE. The first few components of Necklace 1 to appear are ringed on the photo below. All that was found of the original occupant of the grave was a single fragment of unburnt bone, but since jet necklaces are associated with women, it’s likely that that person had been female.

The rest of the necklace was discovered when the Food Vessel was block-lifted. The rest of the necklace was discovered when the Food Vessel was block-lifted. The fact that several of the components lay in an arc, resting on a thin layer of sediment on the stones lining the base of the grave, made the task of reconstructing the necklace easier. It also indicated that the necklace cannot have been around the neck of the deceased: it had been deposited flat. The reasoning for this is that when necklaces were worn, their components end up more jumbled than seen here (as the other jet necklace from Dunragit shows); and the direction in which the arc is facing would make no sense for a body laid out along the long axis of the grave.

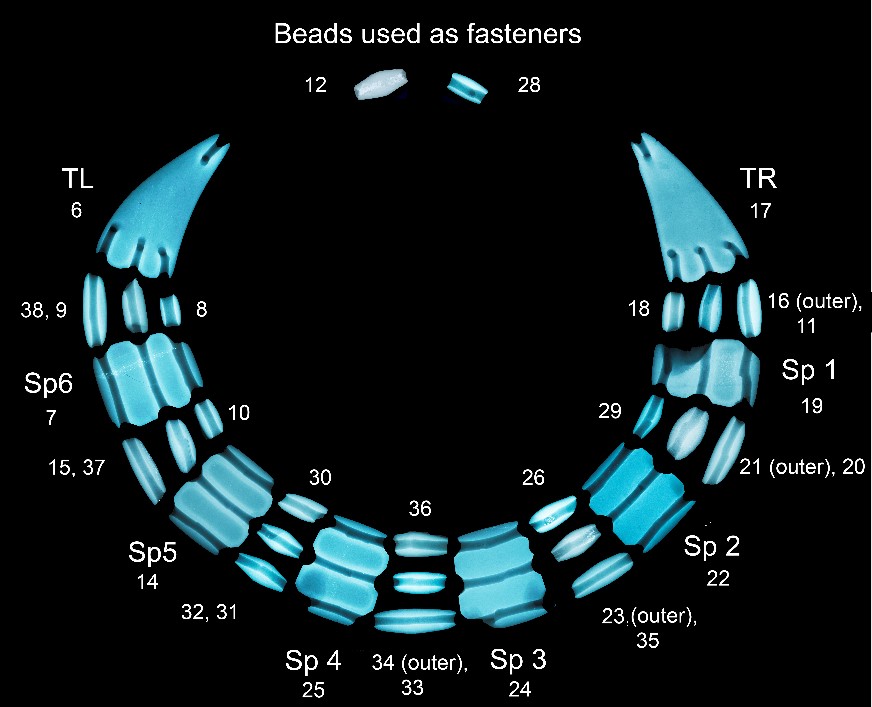

Each of the components was given a Small Find number. In all, the necklace consists of a pair of roughly triangular terminal plates (TL and TR), six spacer plates and 23 beads. Two of the beads must have served as fasteners, since there is only room for 21 beads in the three strands that ran between the plates. The original position of most of the components was fairly easy to work out, and while the positions of a few in the reconstructed necklace are conjectural, the fact that the beads generally increased in length from the inner to the outer strand means that the reconstruction below gives a faithful impression of how the necklace would originally have looked. The internal diameter of the necklace, as shown here, corresponds to the width of an adult female’s neck. Tightly strung, it will have sat on the neck looking like a fairly rigid collar.

No trace of the thread was found on any of the Dunragit jewellery. It will have been organic, strong enough to hold the components tightly strung as a collar, and narrow enough that all three strands could pass through the top holes on the terminal plates – the narrowest of which is around 2.2 mm. Sinew is one possibility, as are several plant-based threads (e.g. willow bast, nettle or linen). Wool would not have been used, since it wasn’t exploited until a particular breed of sheep had emerged, later on during the Bronze Age, and besides it might not have held its tension.

We don’t know how long the necklace would have had to be worn in order to produce the observed degree of wear, but it seems likely that it had not just been worn on special occasions. It might have been passed down over two or more generations, as a precious heirloom.

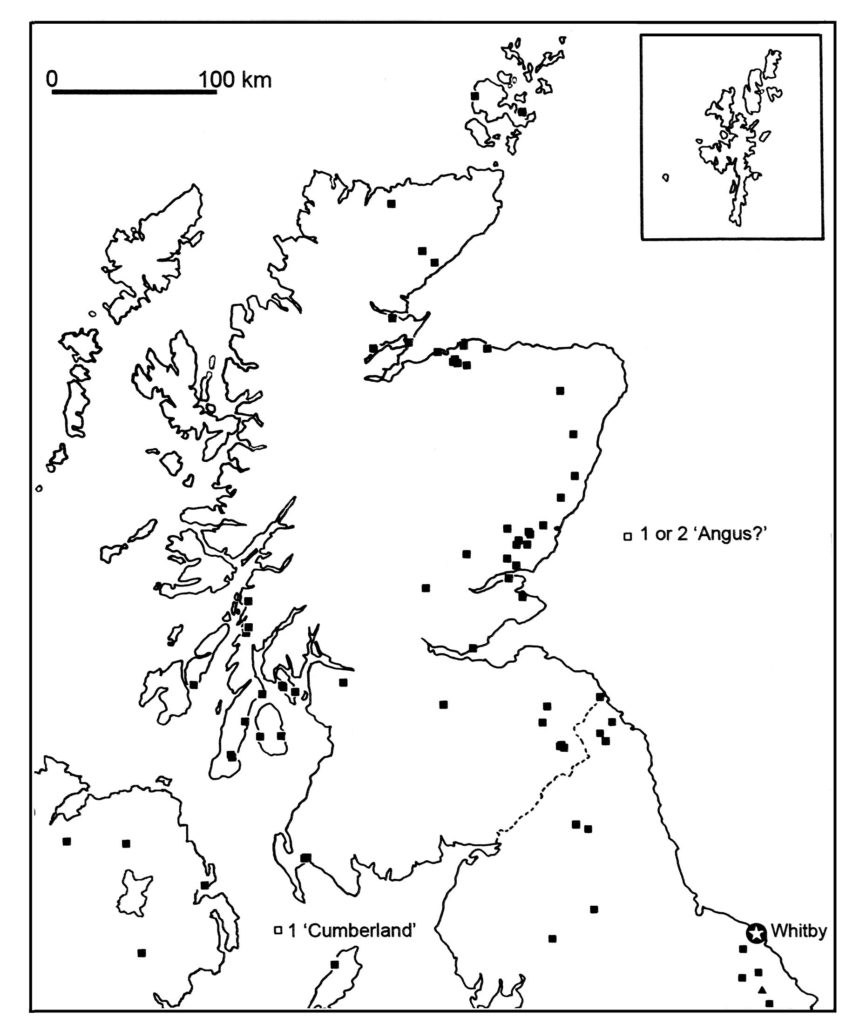

All the components are of jet, and it’s virtually certain that the necklace will have been made in or near Whitby in north Yorkshire – the only significant source of jet in Britain, and a known area where jet jewellery was made. We can tell it is jet from several characteristics: it’s black, light, warm to the touch, has taken a high sheen, and it has cracked in a characteristic way. Dr Lore Toralen’s compositional analysis using X-Ray Fluorescence has confirmed the identification: it has the high zirconium, low iron signature of much of Whitby jet.Parallels for this specific type of spacer-plate necklace, with just three or four strands interspersed with several large spacer plates, are relatively rare but include a necklace from Blindmill in Aberdeenshire and another from Middleton-on-the-Wolds in East Yorkshire.

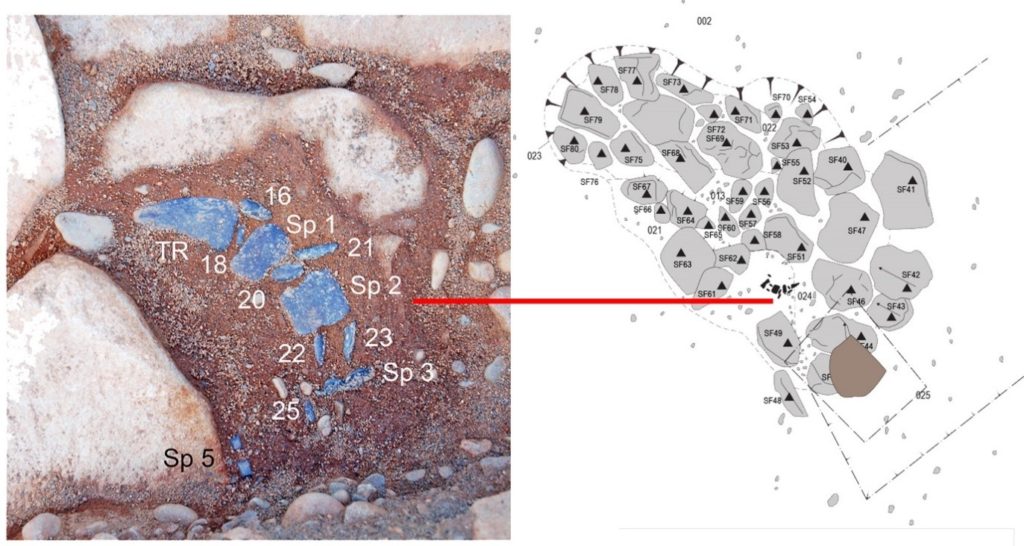

Jet Necklace 2 and bracelet: These were more complicated to reconstruct, because they had clearly been worn on the body in the grave, and as the body decomposed, the jewellery collapsed and its components became intermingled. There are also many more components than in Necklace 1. Necklace 2 consists of a triangular fastener, two terminal plates, a pair of upper spacer plates that increased the number of strands from four to five, a pair of lower spacer plates that increased them from five to seven, plus 108 fusiform (barrel-shaped) beads. The bracelet comprises two terminal plates and 20 beads, in two strands.

The grave 177 was orientated NE-SW, and the jewellery components were found at the NE end, slightly off-centre. No trace of the body survived in the grave, but from the position of the beads and plates there can be no doubt that an unburnt body – again, of a woman, to judge from other graves with spacer-plate jewellery – had been laid on her right side, in a contracted position, with the hands drawn up to the face. Her head was at the NE, looking NW.

Photographs and plans that were created at various stages in the excavation showed how the necklace and bracelet had collapsed as the body decayed. While some components had been moved around a little, probably by the action of worms or rodents, by and large the beads and plates were in their original, post-decay positions.

Photo 1 above shows the mass of necklace and bracelet components indicating where the head and hands were lain.Photo 2 shows the topmost layer of beads and plates, annotated to identify the plates. Note that the triangular fastener and left-hand terminal (TL) have their undersides uppermost: this part of the necklace must have flopped to the floor of the grave when the thread decomposed. Photo 3 shows the next layer down. The TR is pointing away from the rest of the necklace – probably moved by worm or rodent action – and the upper left spacer plate (Sp 1L) that lay under its counterpart has been exposed. The fact that its outer surface is uppermost indicates that the head and shoulders had not lain at 90 degrees to the floor of the grave, but at a less acute angle – meaning that more of the necklace would have been visible to mourners looking in on the grave. Also visible on Photo 3 are the small triangular terminal plates of the bracelet, with SF 176’s perforated lower edge uppermost. The position of these and the bracelet beads, at a relatively low level, is consistent with the wrist in question being close to the neck, with beads from the necklace falling onto it as the body decayed.

As with Necklace 1, Necklace 2 and the bracelet are complete, and the consistency in the material, degree of wear and style of manufacture show that there had been no substitution of replacement elements, as sometimes happens with jet necklaces. X-Ray Fluorescence of one of the necklace beads confirmed that the material is jet, and it was noted that far fewer components showed the extensive surface criss-cross cracking that had been seen on Necklace 1.The beads and plates are far less worn than those on Necklace 1, which suggests that this set of matching necklace and bracelet had not been as old as Necklace 1 when it was buried. But, as we have seen, the necklace and bracelet didn’t look like this when found! It was necessary to do a complex, 3D jigsaw in order to arrive at the re-strung versions that you see here. How was this achieved? Just add time – weeks of it – and 30 years’ experience with Bronze Age jet jewellery…

As with Necklace 1, the inner diameter of the completed necklace corresponds to the width of an adult female’s neck; and this necklace, like Necklace 1, would have sat as a fairly rigid collar.

Necklace 2 is the commonest design of jet spacer-plate necklaces. Some have decoration on their spacer and terminal plates, but this one does not.

The presence of a bracelet, forming a matching set or parure, is rare but there is a good parallel from Campbeltown, and several others are known from Scotland. Normally just one bracelet is present, but at Melfort, just north of Kilmartin Glen in Argyll and Bute, a pair of magnificent sheet bronze bangles, with embossed designs in the shape of fusiform jet beads, was found.

The Dunragit Jet Set: These finds constitute the 55th to 57th examples of Early Bronze Age spacer-plate jewellery of jet (and of materials visually resembling jet) in Scotland. This jewellery was rare and precious, and served to signify the high status of the females who wore it. The Early Bronze Age in Scotland is the earliest time when obvious signs of female special status, such as these magnificent necklaces, were displayed in Scotland (and elsewhere).

As you can see from the map below, there is a cluster of finds of spacer-plate necklaces a little to the north, around the Firth of Clyde and Kilmartin Glen, and a scatter of such necklaces to the west of Galloway in the north of Ireland, along with a recently-discovered example at Berk Farm, Isle of Man. It may be that the source of the wealth that enabled people in the Firth of Clyde and Kilmartin Glen to acquire these necklaces from Whitby was their control over the movement of Irish metal, which travelled up the Great Glen for bronzeworking around the Moray and Cromarty Firths. Other clusters, as in Moray and in Angus and Fife, are in rich agricultural areas. What enabled the Dunragit ‘jet set’ to acquire this precious and valuable jewellery? We don’t know; perhaps they, too, were involved with the movement of Irish metal. But it underlines the fact that the inhabitants of this part of Scotland were wealthy, and they participated in the dominant ‘vocabulary of esteem’ of the time. Jet-setters, indeed!

The kind of jet spacer-plate necklace that is Dunragit Jet Necklace 2 is a skeuomorph (i.e. copy in another material) of the Early Bronze Age gold lunulae which are known mostly from Ireland; a very few gold lunulae are known from Scotland. Here is one, featured on the poster for 1985, Symbols of Power at the Time of Stonehenge exhibition, at the then-named Royal Museum of Scotland.

It’s clear that both of the Dunragit necklaces, and the bracelet, were complete when buried, and they each consist of their original components, without any substitutions. Not all spacer-plate jewellery is found in such a complete state.

We are lucky that the Dunragit jewellery was excavated professionally and with the utmost care; many spacer-plate necklaces were found a long time ago, and dug up with little attention to the precise position of each of the components. One that was found in a cist at Poltalloch in Kilmartin Glen in 1928 was excavated (albeit as carefully as possible) with the aid of a piece of twisted wire, and since the excavator thought that the beads lay in a network pattern, the necklace was re-strung in that way (https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-352-1/dissemination/pdf/vol_063/63_154_181.pdf). That misconception influenced the way in which museums displayed these necklaces for most of the 20th century.

The detailed records made by the GUARD Archaeology excavators at Dunragit enable us not only to reconstruct the jewellery with a fair degree of accuracy, but also to appreciate the differences in the way it was buried, from one grave to the other: set aside from the corpse in the case of one grave, but worn on the body in another grave.