Dr Kenny Brophy is a senior lecturer in Archaeology at the University of Glasgow, whose primary research interests are public archaeology, contemporary archaeology and the Neolithic of Britain. Kenny is the Academic Editor for the A75 Dunragit Bypass post-excavation works and is this month’s guest contributor to the blog.

In the summer of 1999, twenty years ago, I drove down to Wigtownshire to spend a week’s holiday from my job with the aerial survey team of the former Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS), now Historic Environment Scotland (HES), to help with a major excavation at one of the most significant Neolithic cropmark complexes in Scotland – Dunragit. This is a site that had already been close to my heart for a long time, as a Neolithic researcher and cropmark obsessive. I had even been asked on to a show on BBC Radio Scotland to talk about the significance of the cropmarks and why they were ‘Scotland’s Stonehenge’ (clue: they are not!).

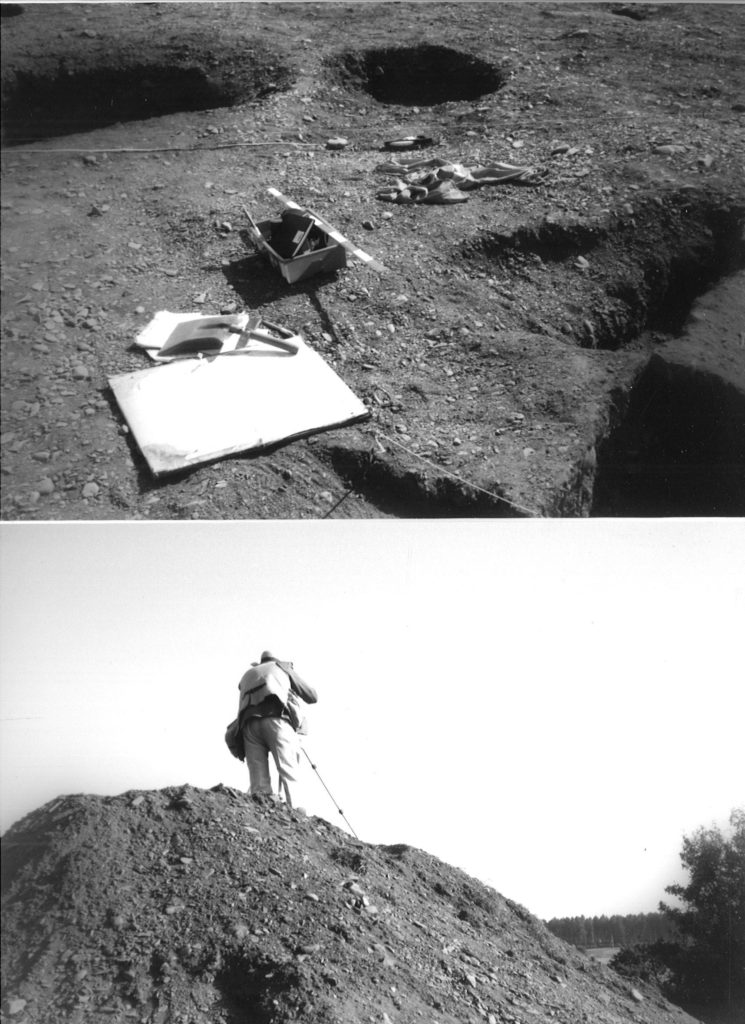

The chance to work with Julian Thomas (now Professor of Archaeology at Manchester University) again was also too good to miss, having served as site supervisor for him at his excavations at Holywood cursus complex and Holm Farm in the two previous summers, both also in Dumfries and Galloway. During my week at Dunragit, I got to dig some Neolithic post-holes which is one of the most pleasurable ways possible to spend a summer’s day!

I have been thinking a lot about this site and that summer recently, because I am now advising GUARD Archaeology on the post-excavation and writing up of their excavations along the route of the new A75 Dunragit Bypass. The significant discoveries made along this road corridor are adding a huge amount of information, depth and context to Thomas’s excavations of the main cropmark complex, published in his 2015 book A Neolithic ceremonial complex in Galloway. Amongst other things he excavated parts of an early Neolithic timber cursus monument (rectangular enclosure dating to about 3800 BC) and a huge triple-boundary timber palisaded enclosure of the late Neolithic (2800-2600 BC); all of this archaeology had been recorded as cropmarks. GUARD Archaeology’s work has added to this considerably.

It was a recent visit to Dunragit with the Neolithic Studies Group that brought home to me the significance of GUARD Archaeology’s discoveries. We visited the Droughduil Mote, a huge flat-topped mound to the south of the main cropmark area. Thomas excavated this (with a minibus load of students from my archaeology department at Glasgow there to help) in 2002, on a hunch, because the mound was aligned upon by the entrance avenue to the Neolithic enclosures he had been excavating to the north. It turned out to be a sand dune that was artificially enhanced in the Neolithic period, an enormous endeavour to create a viewing platform to overlook ceremonies and rituals being carried out nearby. The excavations undertaken for the A75 Dunragit Bypass project in the area between the Droughduil Mote and the Neolithic enclosures of Dunragit and will hopefully shed some light on the activities that took place here in the Neolithic period.

One thing Julian was not able to determine during his three seasons of excavations was – what was going on between the timber enclosures he investigated at Dunragit and the big mound in prehistory? Cropmarks had not been able to fill in the detail of this flat area and a gap of a few hundred metres. A gap now filled by the A75 Dunragit Bypass!

The route of the bypass enabled excavations to take place in this area, known as Droughduil Holdings, in 2014, to help begin to solve the mystery of what lay between the Neolithic timber enclosures at Dunragit and the Mote mound. Right across the road corridor zone, effectively sampling this part of the Neolithic landscape, dozens of pits and post-holes were found. The post-excavation work currently being undertaken by Transport Scotland and GUARD Archaeology will provide dates for this activity, but it seems likely that Neolithic activity is represented here, with possible alignments and even structures identifiable, which will shed light – we hope – on how people were navigating this part of the landscape in the Neolithic period, perhaps part of ritual processions.

The A75 archaeological work as a whole will add a huge amount to our understanding of the major Neolithic complex at Dunragit, but also expand the time-depth of our knowledge of this place, with major Mesolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age discoveries made in the vicinity. Dunragit and Droughduil is not just a Neolithic story but goes back centuries before and runs on centuries after the monuments Julian Thomas focused on. We have come a long way in 20 years. Back then Dunragit was only a set of dark marks amongst the crops on air photographs, a site of potential but essentially an area where the archaeology was as yet poorly understood. Thomas’s excavations got the ball rolling, but it took the broader landscape sampling offered by the construction of the new bypass to open up insights into the context of the timber enclosures.

In turn, the amazing discoveries made by GUARD Archaeology on behalf of Transport Scotland will help us not just better understand what was happening at Dunragit thousands of years ago, but also help us say lots of new things about Scotland in prehistory.