ARO31 Cover

The results of Brian Hope-Taylor’s excavation of the Mote of Urr, undertaken 65 years ago, have now been published in GUARD Archaeology’s publications journal ARO. Excavations at Mote of Urr, near Dalbeattie in Dumfries and Galloway were undertaken in 1951 and 1953. The earliest phase of occupation comprised the construction of the motte-and-bailey castle and its destruction by fire, after which a large central stone-lined pit for an oven, furnace, kiln or beacon was dug. The pit continued in use when the motte was heightened and enclosed by a clay bank and palisade during a second phase of occupation. In its final phase, when the motte was heightened again, a possible double palisade enclosing the summit of the motte was found.

Mote of Urr © Historic Environment Scotland

Hope-Taylor dated the construction and earliest occupation at Mote of Urr to the late twelfth century, with continued occupation into the fourteenth century. Although Mote of Urr seems to have been the centre for Walter de Berkeley’s lordship of Urr in the second half of the twelfth century, nothing as early as this was identified in the pottery and artefacts recovered from the excavations. Only two radiocarbon dates from the earliest phase of occupation support the twelfth-century occupation at the motte, which probably terminated during the rebellion in Galloway in 1174. A radiocarbon date of AD 1215-1285 from a later pit suggests that the heightening and strengthening of the motte took place in the thirteenth century. Pottery evidence suggests occupation in the thirteenth century, continuing into the second half of the fourteenth century, if not into the fifteenth century.

The Mote of Urr excavation team. Brian Hope-Taylor is in the back row, second from the left © Historic Environment Scotland

‘Brian Hope-Taylor was a charismatic and perspicacious scholar, though like some other archaeologists he did not find it easy to write up the results of his excavations for final publication,’ said Professor Barbara Crawford of the University of St Andrews and University of the Highlands and Islands. ‘It is therefore with appreciation of Brian Hope-Taylor’s skills as a teacher and more particularly as an excavator of important medieval sites in northern England and southern Scotland that I welcome this publication. It will advance our understanding of these impressive mounds in the landscape and perpetuate Hope-Taylor’s legacy in exploring such lordship sites.’

The full results of this research, which was funded by Historic Environment Scotland, ARO31: Brian Hope-Taylor’s archaeological legacy: Excavations at Mote of Urr, 1951 and 1953 by David Perry with contributions by Simon Chenery, Derek Hall, Mhairi Hastie, Davie Mason, Richard D Oram, and Catherine Smith is freely available to download from the ARO website – Archaeology Reports Online.

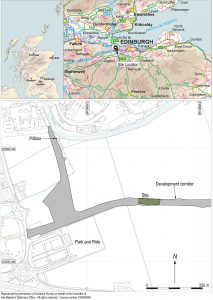

Archaeological investigations coupled with historical research of Newcraighall on the south-east edge of Edinburgh reveal a complex story of land use changes from prehistory to the present day.

Archaeological investigations coupled with historical research of Newcraighall on the south-east edge of Edinburgh reveal a complex story of land use changes from prehistory to the present day. These included various sized coal pits or shafts, and the foundations of four colliery buildings, arranged around a now infilled mineshaft on the southern site. Elements of a designed landscape associated with Brunstane House included a ha-ha that traversed the northern site. The presence of several large culverts may also have connections with both landscape alterations and the coal-mining industry. Fragments of curved and linear ditches appear to be remnants of earlier field systems dating from the medieval and post-medieval periods and associated with extensive remnants of broad rig cultivation found across the two areas.

These included various sized coal pits or shafts, and the foundations of four colliery buildings, arranged around a now infilled mineshaft on the southern site. Elements of a designed landscape associated with Brunstane House included a ha-ha that traversed the northern site. The presence of several large culverts may also have connections with both landscape alterations and the coal-mining industry. Fragments of curved and linear ditches appear to be remnants of earlier field systems dating from the medieval and post-medieval periods and associated with extensive remnants of broad rig cultivation found across the two areas. The historical research demonstrates the complexities of landownership with evidence of the development of coal mining and coal ownership and the social and economic realities of the times. Examination of papers relating to Brunstane House showed that they had direct bearing on the understanding and dating of the landscaping features and other groundworks, including changes to the estate boundaries and the runrig system. A labourer’s diary from the winter of 1735-6 was an especially interesting find from the point of view of what work was undertaken on the estate, by whom and for how much.

The historical research demonstrates the complexities of landownership with evidence of the development of coal mining and coal ownership and the social and economic realities of the times. Examination of papers relating to Brunstane House showed that they had direct bearing on the understanding and dating of the landscaping features and other groundworks, including changes to the estate boundaries and the runrig system. A labourer’s diary from the winter of 1735-6 was an especially interesting find from the point of view of what work was undertaken on the estate, by whom and for how much. Newly published archaeological research from excavations undertaken at the Udal in North Uist reveals some of the hardships of life in Neolithic and early Bronze Age Scotland. Two burial cairns held the remains of individuals dating to the second millennium BC. Scientific analyses of these individuals demonstrate the dramatic effect that environmental stresses had on the community.

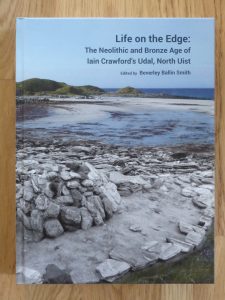

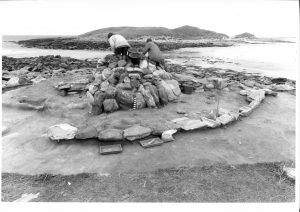

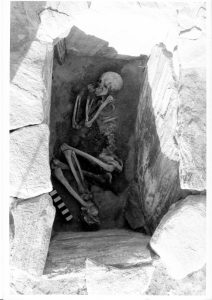

Newly published archaeological research from excavations undertaken at the Udal in North Uist reveals some of the hardships of life in Neolithic and early Bronze Age Scotland. Two burial cairns held the remains of individuals dating to the second millennium BC. Scientific analyses of these individuals demonstrate the dramatic effect that environmental stresses had on the community. The accumulation of sand and the flooding episode separated the end of the late Neolithic settlement from the beginning of the early Bronze Age, around 2400 BC. Sometime after the creation of the beach, a burial cairn was built, under which a young man was laid to rest in stone cist. This large round mound of stone and turf was the largest man-made structure on the Udal peninsula. By erecting the cairn, the inhabitants that lived in the area claimed back the landscape as theirs. The monument was meant to be enduring and it lasted approximately 4000 years before coastal erosion threatened it, necessitating its excavation.

The accumulation of sand and the flooding episode separated the end of the late Neolithic settlement from the beginning of the early Bronze Age, around 2400 BC. Sometime after the creation of the beach, a burial cairn was built, under which a young man was laid to rest in stone cist. This large round mound of stone and turf was the largest man-made structure on the Udal peninsula. By erecting the cairn, the inhabitants that lived in the area claimed back the landscape as theirs. The monument was meant to be enduring and it lasted approximately 4000 years before coastal erosion threatened it, necessitating its excavation. ‘Our Neolithic and Bronze Age ancestors lived through climate change events such as dramatic sea-level rise and increased storminess, and trauma such as loss of fields, crops and animals. They had to relocate their settlement and houses to safer areas,’ said Beverley. ‘How the inhabitants of the Udal survived during the Bronze Age will be part of the research on the next Udal site – the South mound.’

‘Our Neolithic and Bronze Age ancestors lived through climate change events such as dramatic sea-level rise and increased storminess, and trauma such as loss of fields, crops and animals. They had to relocate their settlement and houses to safer areas,’ said Beverley. ‘How the inhabitants of the Udal survived during the Bronze Age will be part of the research on the next Udal site – the South mound.’

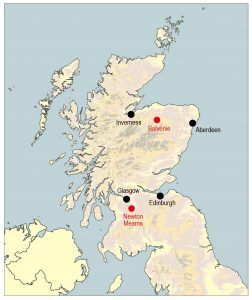

Recently published research from two sites at opposite ends of Scotland reveals new evidence for Bronze and Iron Age landscapes.

Recently published research from two sites at opposite ends of Scotland reveals new evidence for Bronze and Iron Age landscapes.

Recently published research by Bob Will of GUARD Archaeology reveals the discovery of the complex history of settlement at a place in the Lothians of Scotland, from the Neolithic through the Bronze Age and Iron Age into the early medieval period.

Recently published research by Bob Will of GUARD Archaeology reveals the discovery of the complex history of settlement at a place in the Lothians of Scotland, from the Neolithic through the Bronze Age and Iron Age into the early medieval period.

Two truncated roundhouses near the north end of the site were dated to the Iron Age. An associated fragment of a miniature quern was recovered; these tend to be found in the east of Scotland during the Iron Age. The final phase of activity on-site comprised the remains of two corn-drying kilns, dated to between the sixth and eighth centuries AD, that survived as oval pits containing considerable quantities of burnt and charred cereal grains. Associated with the better-preserved kiln was a rim sherd of coarse pottery and two fragments from a rough quern.

Two truncated roundhouses near the north end of the site were dated to the Iron Age. An associated fragment of a miniature quern was recovered; these tend to be found in the east of Scotland during the Iron Age. The final phase of activity on-site comprised the remains of two corn-drying kilns, dated to between the sixth and eighth centuries AD, that survived as oval pits containing considerable quantities of burnt and charred cereal grains. Associated with the better-preserved kiln was a rim sherd of coarse pottery and two fragments from a rough quern. While the archaeological investigations provided evidence for occupation of this place over a long period of time, it was surprising that little evidence for settlement from the Roman occupation of southern Scotland was encountered, considering the presence nearby of a Roman fort, milestone and temporary camps. The archaeological remains from the excavation nevertheless provide a palimpsest of prehistoric and early medieval occupation and support similar occupation and settlement evidence from the wider region. The early medieval date for the corn-drying kilns provides direct evidence for settlement and agriculture, as well as a domestic setting for the long-cist cemetery at Catstane to the north. Together with another nearby long-cist cemetery to the south and contemporary field boundaries near Gogar Church, the results are combining to gradually fill out a picture of sustained settlement and agriculture in this area of the Lothians during the early medieval period.

While the archaeological investigations provided evidence for occupation of this place over a long period of time, it was surprising that little evidence for settlement from the Roman occupation of southern Scotland was encountered, considering the presence nearby of a Roman fort, milestone and temporary camps. The archaeological remains from the excavation nevertheless provide a palimpsest of prehistoric and early medieval occupation and support similar occupation and settlement evidence from the wider region. The early medieval date for the corn-drying kilns provides direct evidence for settlement and agriculture, as well as a domestic setting for the long-cist cemetery at Catstane to the north. Together with another nearby long-cist cemetery to the south and contemporary field boundaries near Gogar Church, the results are combining to gradually fill out a picture of sustained settlement and agriculture in this area of the Lothians during the early medieval period. Recently published research reveals a range of artefacts recovered from two sites on the edge of the medieval burgh and castle at Stirling.

Recently published research reveals a range of artefacts recovered from two sites on the edge of the medieval burgh and castle at Stirling. This section of footpath runs behind Cowane’s Hospital next to the Church of the Holy Rude and on the perceived line of the Stirling town wall, which was constructed sometime in the sixteenth century.

This section of footpath runs behind Cowane’s Hospital next to the Church of the Holy Rude and on the perceived line of the Stirling town wall, which was constructed sometime in the sixteenth century. One of the more unusual artefacts to be recovered from the Back Walk was a WWI military belt buckle. The military buckle is from the Austrian army and has the double headed imperial eagle and the Austrian coat of arms and is one that was standard issue during WWI.

One of the more unusual artefacts to be recovered from the Back Walk was a WWI military belt buckle. The military buckle is from the Austrian army and has the double headed imperial eagle and the Austrian coat of arms and is one that was standard issue during WWI.