Hadrian’s Wall is often blamed for splitting Ancient Britain in two but newly published archaeological research reveals that the peoples of Scotland and England were already culturally divergent long before the Romans arrived in Britain.

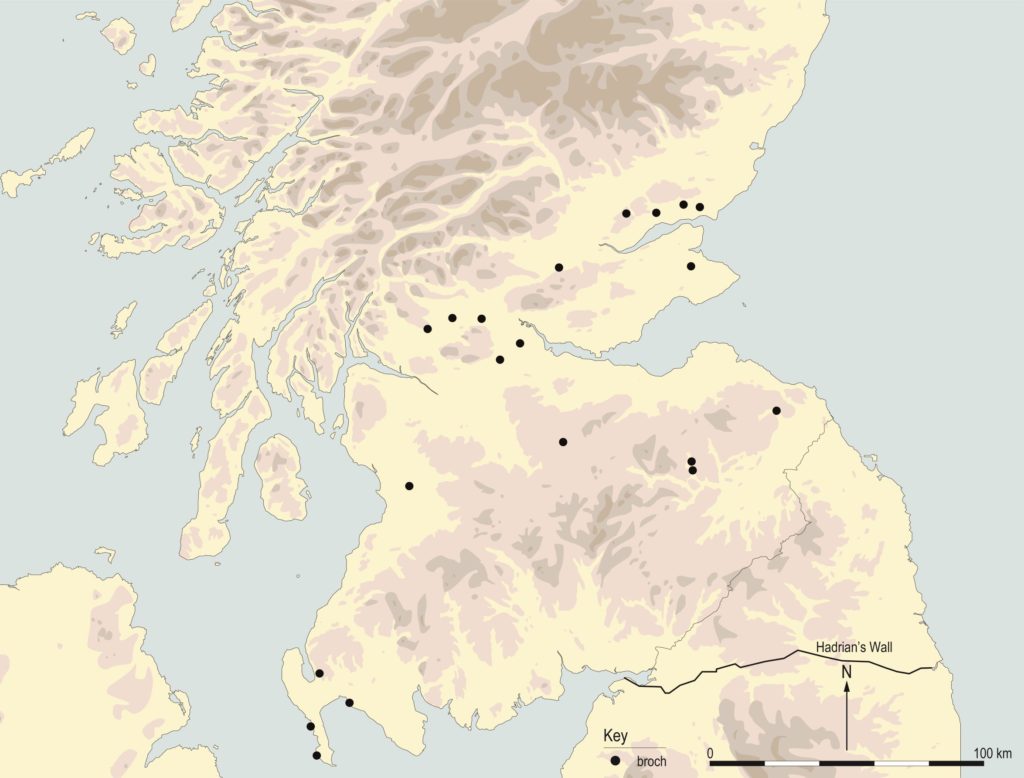

An array of brochs, duns, crannogs and souterrains are found widely across Scotland but are not evident in northern England or further south. Surprisingly, that various types of Iron Age settlement do not breach the Anglo-Scottish border is something that has not been examined in detail, until now.

‘The underlying implication of the settlement distribution patterns is that Iron Age societies across Scotland were open to the building and occupation of brochs, crannogs, duns and souterrains but that Iron Age societies further south were not,’ said GUARD Archaeologist Ronan Toolis, who conducted the research. ‘This was the result of cultural choices taken by households and communities, not environmental constraints, and suggests that Iron Age societies north and south of the Tweed–Solway zone were perceptibly dissimilar. And while the density of brochs, crannogs, duns and souterrains varies across Scotland, this reflects not so much a patchwork but a spectrum of settlement patterns.’

These distinctive differences in the archaeological record are especially significant because the construction of crannogs and souterrains during the 4th-2nd centuries BC demonstrates that this divergence occurred long before the Roman frontier zone may have severed societies.

‘The archaeological divergence does not equate with the line of Hadrian’s Wall but rather more closely with the Anglo-Scottish border,’ added Dr Toolis. ‘The Wall instead follows probably the best strategic course through a broader zone of cultural divergence.’

And this may have played a crucial part in explaining why the Romans failed to absorb Scotland into their empire, despite three major military campaigns that appear, at least in Roman accounts, to have been overwhelmingly successful. This failure is often attributed to the changing political and military priorities of Rome but it may owe more to the nature of Iron Age society in Scotland, which archaeologists are beginning to recognise was anarchic in nature – not chaotic but composed of autonomous households and communities lacking institutionalised leadership. Unlike the tribal kingdoms the Romans encountered to the south.

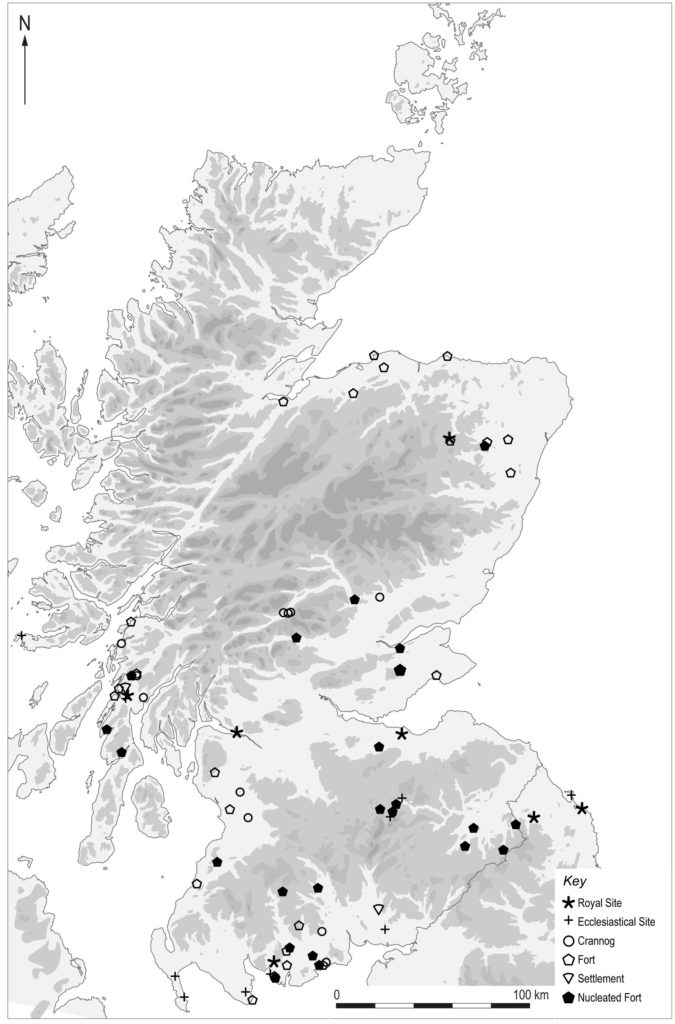

Clear evidence for the adoption of Roman culture does not occur in Scotland until the 5th century AD, after the Romans had abandoned Britain, when secular as well as ecclesiastical Latin inscribed stones, bearing Latinised names of indigenous inhabitants, and Christian terminology and symbols, were erected across southern Scotland.

‘This only occurred when Iron Age society in Scotland had become hierarchical,’ said Dr Toolis. ‘The evidence implies that far from being passive participants in acculturation, it was only with their active participation and likely at their own instigation and on their own terms, that communities in Scotland truly adopted aspects of Roman culture.’

Moreover, expressions of power and prestige distinctive to early medieval Scotland suggest profound cultural divergence continued in the centuries that followed the demise of Roman Britain.

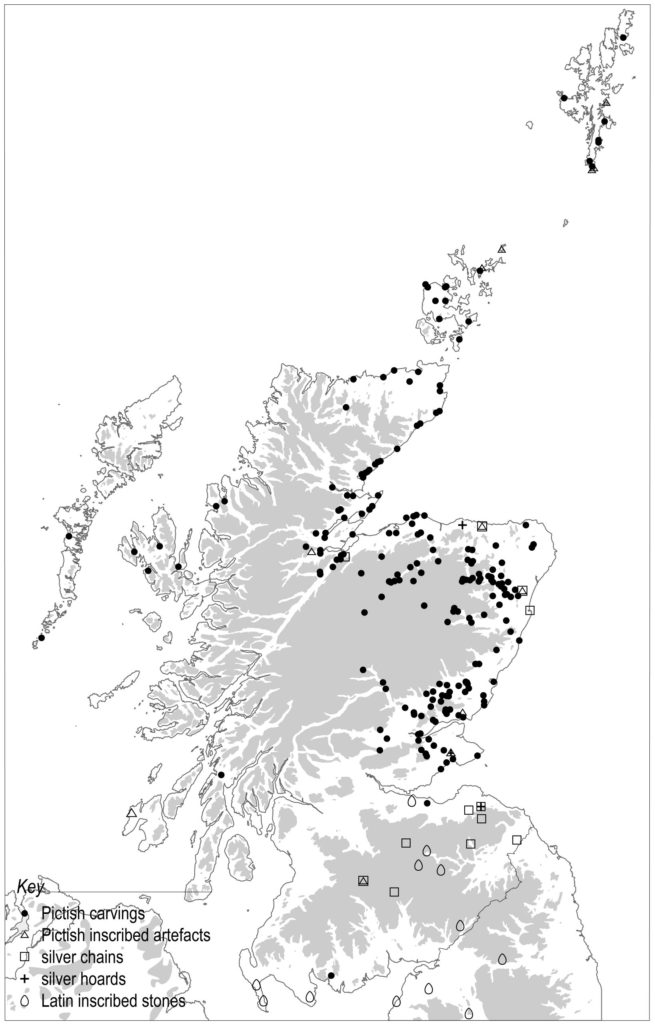

Pictish symbols, whether carved on stone or inscribed upon artefacts like massive silver chains and silver ornaments, are only found in Scotland. While these are overwhelmingly concentrated north of the Forth, they are also encountered within non-Pictish contexts to the south and west in the Lothians, Lanarkshire, Galloway and Argyll. The direction of influence was not one-way. Massive silver chains, which are also unique to Scotland, are concentrated in the south-east of the country, reflecting their cultural origin here, the result of the appropriation of Roman silver as a way of expressing status and power. That silver chains are also found north of the Forth but not south of the Tweed and Solway demonstrates yet again mutual cultural values in the expression of power and prestige among the Britons of southern Scotland and the Picts of northern Scotland, but not apparent among the Britons, Angles and Saxons of England and Wales.

Nucleated forts, a type of early medieval hillfort unique to Scotland, are also absent south of the border. These often occur in discrete clusters of elite settlements – in Galloway, Argyll, the Scottish Borders, Fife, Tayside and Aberdeenshire. Excavations have revealed several of these forts to be royal strongholds with evidence for international trade, the manufacturing of gold and silver jewellery and royal inauguration rites. Similar sized clusters of prominent households occupying brochs across lowland Scotland during the first two centuries AD may represent an Iron Age precursor to the pre-eminent households that emerged in the 5th–7th centuries AD.

‘It may be that the clusters of early medieval elite settlements reflect how society in Scotland was replicating a process of households accruing power and status that had been arrested in development, either because of Roman aggression or internal social upheaval, during the early centuries AD,’ said Dr Toolis.

‘While there existed cultural affinity in some aspects north and south of the border and regional variation is apparent within Scotland itself,’ added Dr Toolis, ‘these do not negate the cultural divergence apparent north and south of the border and the aspects of cultural affinity that the regions of Scotland uniquely share. Just as it is possible for local patterns to be distinguished from regional trends in Iron Age culture in Scotland, so too is it possible to recognise national trends. However, culture should not be conflated with identity. The peoples of early medieval Scotland may have separately identified as Britons, Picts and Scots but they nevertheless shared cultural traits unique to Scotland.’

The archaeological evidence suggests that Hadrian’s Wall was not a cause but instead an effect of existing cultural differences between the peoples of what later became Scotland and England, and this cultural divergence continued beyond into the medieval period. Separate cultural trajectories led to the separate formations of the two kingdoms, entirely independent of Hadrian’s Wall.

Shifting perspectives on 1st-millennia Scotland by Ronan Toolis is published in the latest Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.