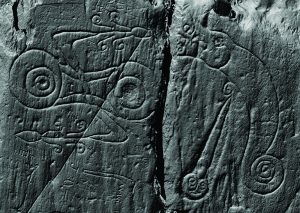

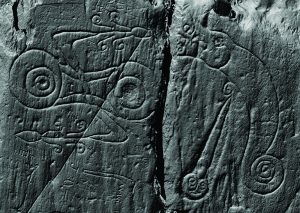

A laser scan image of the Pictish symbols carved at Trusty’s Hill, comprising a z-rod-and-double-disc symbol on the left and a dragon-pierced-by-a-sword symbol on the right © DGNHAS / CDDV

Archaeological research led by GUARD Archaeology has just been published which reveals the location of a hitherto lost early medieval kingdom that was once pre-eminent in Scotland and Northern England.

The kingdom of Rheged is probably the most elusive of all the sixth century kingdoms of Dark Age Britain. Despite contributing a rich source of some of the earliest medieval poetry to be composed in Britain – the poetry of Taliesin who extolled the prowess of its king, Urien of Rheged – and fragments of early medieval historical records of Urien’s dominance in southern Scotland and northern England, the actual location of Rheged has long been shrouded in mystery.

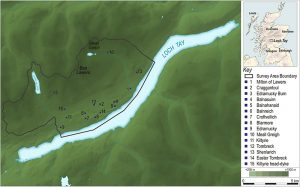

While many historians have assumed it was centred around Carlisle and Cumbria, no evidence has ever been found to back this up. However, new archaeological evidence from the excavation of Trusty’s Hill Fort at Gatehouse of Fleet in Dumfries and Galloway now challenges this assumption.

‘What drew us to Trusty’s Hill were Pictish symbols carved on to bedrock here, which are unique in this region and far to the south of where Pictish carvings are normally found,’ said Ronan Toolis of GUARD Archaeology, who led the excavation which involved the participation of over 60 volunteers. ‘The Galloway Picts Project was launched in 2012 to recover evidence for the archaeological context of these carvings but far from validating the existence of ‘Galloway Picts’, the archaeological context revealed by our excavation instead suggests the carvings relate to a royal stronghold and place of inauguration for the local Britons of Galloway around AD 600. Examined in the context of contemporary sites across Scotland and northern England, the archaeological evidence suggests that Galloway may have been the heart of the lost Dark Age kingdom of Rheged, a kingdom that was in the late sixth century pre-eminent amongst the kingdoms of the north.’

The excavation revealed in the decades around AD 600, the summit of the hill was fortified with a timber-laced stone rampart. Around the same time supplementary defences and enclosures were added to its lower-lying slopes transforming Trusty’s Hill into a nucleated fort, a type of fort in Scotland that has been recognised by archaeologists as high status settlements of the early medieval period.

Anyone approaching the summit of Trusty’s Hill passed between a rock-cut basin on one flank and an outcrop on which two Pictish symbols were carved on the other. This formed a symbolic entranceway, a literal rite of passage, where rituals of royal inauguration were conducted. On entering the summit citadel one may have been greeted with the sight of the king’s hall at the highest part of the hill on the west side, where feasting took place, and the workshop of his master smith occupying a slightly lower area on the eastern side, where gold, silver, bronze and iron were worked into objects. The layout of this fort was complex, each element deliberately formed to exhibit the power and status of its household.

The excavation also found the remains of a workshop that was producing high status metalwork of gold, silver, bronze and iron. The royal household here was also part of a trade network that linked western Britain with Ireland and Continental Europe. In fact, research now shows that over the late sixth and early seventh centuries AD Gaulish merchants were making a beeline for the Galloway coast, ignoring Cumbria entirely. The excavation revealed that one of the reasons for this may have been to acquire materials like copper and lead. Isotope analysis of a lead ingot found during the excavation of Trusty’s Hill was found to have originated in the Leadhills of south-west Scotland, demonstrating that this mineral source was being mined and used to make leaded bronze objects at this time.

Other activities apparent at Trusty’s Hill included the spinning of wool, preparation of leather and feasting. The diet of this early medieval household, with the predominant consumption of cattle over sheep and pigs, and oats and barley rather than wheat, was largely indistinguishable from their Iron Age ancestors.

‘The people living at Trusty’s Hill were not engaged in agriculture themselves,’ said excavation co-director Dr Christopher Bowles, Scottish Borders Council Archaeologist. ‘Instead, this household’s wealth relied on their control of farming, animal husbandry and the management of local natural resources – minerals and timber – from an estate probably spanning the wider landscape of the Fleet valley and estuary. Control was maintained by bonding the people of this land and the districts beyond to the royal household, by gifts, promises of protection and the bounties of raiding and warfare.’

It is in this context that the Pictish symbols at Trusty’s Hill can now be viewed. The new analysis of the symbols here leave no doubt that the symbols are genuine early medieval carvings, likely created by a local Briton, melding innovation, contacts with Atlantic Europe and deep seated traditions.

‘The literal meaning of the symbols at Trusty’s Hill will probably never be known. There is no Pictish Rosetta Stone,’ said Ronan Toolis. ‘But they provide significant evidence for the initial cross cultural exchanges that forged the notion of kingship in early medieval Scotland.’

The location of the symbols at the entranceway to the summit of Trusty’s Hill and opposite a rock-cut basin, mirrors the context of the inauguration stone at Dunadd, the royal centre for the kings of Dalriada, the early Scots kingdom that once covered what is now Argyll and Bute. The imported goods and production of fine metalwork at Trusty’s Hill is comparable in quality to Dunadd, showing that these two royal households were of equal status. Dunadd’s Pictish boar, footprint, ogham and rock-cut basin at the entrance to the summit enclosure are best viewed as a set of royal regalia where the rituals of inauguration took place. The only other Pictish carvings located outside Pictland were found near Edinburgh Castle Rock; another site attested by archaeological and historical evidence to be a royal stronghold of the sixth to early seventh centuries AD. Close comparisons can also now be drawn with the early sixth century royal site at Rhynie in the heart of what was once Pictland.

The 2012 excavation at Trusty’s Hill sought to reveal the archaeological context for the Pictish style carvings. They succeeded in showing that the site was very likely a royal stronghold and place of inauguration of the local Britons of Galloway.

A cluster of contemporary Dark Age sites, such as Whithorn, Kirkmadrine and the Mote of Mark, is now known in Galloway. Trusty’s Hill is the only one of these where there is evidence of royal inauguration and suggests that this site was at the apex of a local social hierarchy. The new evidence from Trusty’s Hill now provides a political context to the wealth and complexity of Galloway during the sixth century, the attraction of the region to continental merchants, and Galloway’s claim as the cradle of Christianity in Scotland. The archaeological record for the establishment of Christianity in southern Scotland suggests that its elite communities were literate and well connected internationally. This could not have occurred without a powerful secular presence providing land and resources. With the corroboration of the literary, historical and archaeological evidence, we begin to see the tantalising clues to a vibrant and dynamic culture that is entirely consistent with Rheged, a kingdom that was pre-eminent in northern Britain in the later sixth century but which faded into obscurity through the course of the seventh century. The deliberate and spectacular destruction of Trusty’s Hill and the nearby contemporary fort at the Mote of Mark in the seventh century AD, which can also be surmised for a number of similar forts in Galloway, is a visceral reminder that the demise of this kingdom in the early seventh century AD came with sword and flame.

‘The new archaeological evidence from Trusty’s Hill enhances our perception of power, politics, economy and culture at a time when the foundations for the kingdoms of Scotland, England and Wales were being laid,’ said Dr Bowles. ‘The 2012 excavations show that Trusty’s Hill was likely the royal seat of Rheged, a kingdom that had Galloway as its heartland. This was a place of religious, cultural and political innovation whose contribution to culture in Scotland has perhaps not been given due recognition. Yet the influence of Rheged, with Trusty’s Hill at its secular heart, Whithorn as its religious centre, Taliesin its poetic master and Urien its most famous king, has nevertheless rippled through the history and literature of Scotland and beyond.’

The Lost Dark Age Kingdom of Rheged by Ronan Toolis and Christopher Bowles is published by Oxbow Books.

The book launch of The Lost Dark Age Kingdom of Rheged is taking place at 2-4pm on Saturday 21 January 2017 at the Murray Arms Hotel, Gatehouse of Fleet.

For more information about the Galloway Picts Project, visit the Galloway Picts website.

The Galloway Picts Project was supported by the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society, the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, GUARD Archaeology Ltd, the Mouswald Trust, the Hunter Archaeological & Historical Trust, the Strathmartine Trust, the Gatehouse Development Initiative, the John Younger Trust, the Galloway Preservation Society and Historic Environment Scotland.