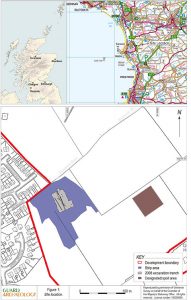

Between 2008 and 2012 archaeological excavations at Barassie near Troon revealed Mesolithic pits, early Neolithic structures, middle to late Neolithic pits, and Bronze Age pits and boundary ditches. The results of these excavations were recently published and expands our knowledge of prehistoric settlement along the west coast of central Scotland.

Prior to this work little was known of the site’s archaeological potential. There were no known archaeological remains. Mesolithic artefacts were recorded about 200m to the south and a socketed late Bronze Age axe was discovered to the south-west. North-west of the site, a cinerary urn had been found. However, in recent years several new prehistoric sites had been discovered along the west coast of Scotland on raised beach areas similar to Barassie, such as at Girvan, Ayr Academy and Monkton, so exploratory trenches were made prior to housing developments by Stewart Milne Homes and Lynch Homes.

Subsequent to the excavation, specialist analysis of the finds demonstrates that the raised beach area at Barassie was visited and exploited over six millennia from the Mesolithic period in the eighth millennium BC through to the Bronze Age in the second millennium BC.

Barassie was a favoured place. The archaeological remains from the Mesolithic to the Bronze Age were situated on a raised beach with an open aspect to the sea and fresh water sources close at hand. Its slight elevation and other resources including land that was suitable for agriculture and settlement seem to be the main factors that drew prehistoric people to the site repeatedly.

The use of the land and its natural resources altered through time; from a hunter-gatherer economy in the Mesolithic to an agricultural based society in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages. The evidence for human occupation may have been intermittent across the landscape but the presence of the long boundary ditches during the Bronze Age suggest that the land belonged to individuals who marked the edges of their territory or fields and by doing so were at least attempting to establish a degree of permanence.

Later damage caused by agricultural drainage and ploughing together with the canalisation and re-directing of Barassie Burn has affected the preservation of the archaeological record, providing us with an incomplete picture. This curtailed view of the site has made the understanding and interpretation of the early Neolithic settlement as well as the earlier and later activities occurring on the site difficult. In a palimpsest site such as Barassie even radiocarbon dating results can become double-edged swords. On one hand, they can provide reliable dates for features but they can also highlight the constraints faced by the archaeologist when interpreting a site where there are few recognisable patterns or focal points of activities and structures.

In spite of these issues, this site highlights the importance of settlement over time even at the local level, and the fact that exotic goods from distant places were acquired as part of social interaction and the wider economy of the time. During the Neolithic, Barassie was part of a regional and longer distance system of exchange that promoted actions or beliefs marked by artefacts deposited in pits. Until recently the central west coast area had not received much archaeological input in comparison with other areas of Scotland, and now Barassie can be added to the growing corpus of sites from this region that provide glimpses of a complex past.

Excavation of a Bronze Age plain urn at Barrassie

The full results of this research, Prehistoric settlement and ritual activities at Barassie, South Ayrshire by Iraia Arabaolaza was recently published in the Scottish Archaeological Journal (volume 39, 2017).