Archaeologists from GUARD Archaeology Ltd, working for Scottish Water, have uncovered the remains of one of the earliest houses in East Ayrshire. Dating to around the early Neolithic period (3,500-4000 BC), these archaeological remains were uncovered in countryside near Kilmarnock while Scottish Water was working on an ongoing £120M project to upgrade the water mains network between Ayrshire and Glasgow.

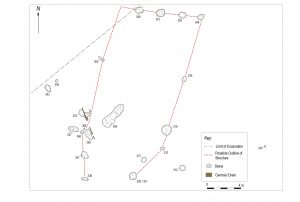

Eight areas of archaeology were observed by the GUARD Archaeologists, who were monitoring the excavation works for the new pipeline. These included some prehistoric burnt spreads and pits but of particular note was the discovery of early Neolithic carinated bowl fragments in a number of post-holes forming part of a rectangular building near Hillhouse farm. This rectilinear hall, which measured 14 m in length and 8 m across, belongs to a type of house built by the first farming communities in Scotland.

‘Heavily truncated by millennia of ploughing, only the deepest parts of some of the post-holes survived, arranged in a rectangular plan and containing sherds of early Neolithic pottery, hazelnut shell and charcoal,’ said GUARD Archaeology excavation director Kenneth Green. ‘The width and depth of these post-holes indicated that they once held very large upright timber posts, suggesting that this building was once a large house, probably home to an extended family or group of families.’

Up until this time, during the earlier Mesolithic period (c. 8000-4000 BC), Scotland was inhabited by small groups of hunter gatherers, who led a nomadic lifestyle living off the land. The individuals that built this Neolithic house were some of the earliest communities in Ayrshire to adopt a sedentary lifestyle, clearing areas of forest to establish farms, growing crops such as wheat and barley and raising livestock such as cattle, sheep, goats and pigs.

Up until this time, during the earlier Mesolithic period (c. 8000-4000 BC), Scotland was inhabited by small groups of hunter gatherers, who led a nomadic lifestyle living off the land. The individuals that built this Neolithic house were some of the earliest communities in Ayrshire to adopt a sedentary lifestyle, clearing areas of forest to establish farms, growing crops such as wheat and barley and raising livestock such as cattle, sheep, goats and pigs.

‘The pottery recovered from the Neolithic house are sherds of Carinated Bowl, one of the earliest types of pottery vessels ever to be used in Britain’ added Kenneth Green. ‘Traces of milk fat have been found in other carinated bowls found elsewhere in Scotland. Carinated Bowls are distributed across Scotland but very few have been found in the west so Hillhouse represents an important discovery.’

Further post-excavation analyses of the pottery charcoal and environmental samples taken during the excavation may reveal the precise date when the house was occupied and provide other insights that will improve our understanding of the spread of farming settlements across Neolithic Scotland.

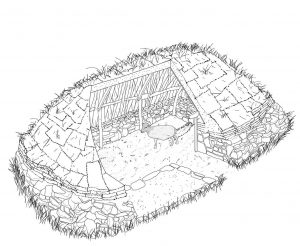

Newly published research by GUARD Archaeology has revealed the complex history of a turf and stone-built medieval building. Sherds of pottery obtained from the floor of the structure suggest it was in use during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries AD. However, its construction is similar to other excavated buildings dated to the early medieval period. Radiocarbon dates obtained from several features and deposits ranged from the Bronze Age, through the Iron Age to the medieval period. The structure is an uncommon survivor of medieval rural settlement that is rarely excavated in Scottish archaeology.

Newly published research by GUARD Archaeology has revealed the complex history of a turf and stone-built medieval building. Sherds of pottery obtained from the floor of the structure suggest it was in use during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries AD. However, its construction is similar to other excavated buildings dated to the early medieval period. Radiocarbon dates obtained from several features and deposits ranged from the Bronze Age, through the Iron Age to the medieval period. The structure is an uncommon survivor of medieval rural settlement that is rarely excavated in Scottish archaeology. The rareness of the Kintore medieval building is predominantly due to the lack of identification of them in the landscape, the result of their construction using perishable materials such as clay and turf, and changes in land-use which have led to their destruction. Often the stones from these buildings have been systematically removed over time, or the buildings replaced with new structures, or adapted to different uses. The survival of the Kintore building, despite being partially damaged and robbed, might be due to the marginal nature of the ground it sits on, which is very boggy in places and contains a large amount of stone, both above and below ground, which inhibited ploughing that might otherwise have removed all traces of the building.

The rareness of the Kintore medieval building is predominantly due to the lack of identification of them in the landscape, the result of their construction using perishable materials such as clay and turf, and changes in land-use which have led to their destruction. Often the stones from these buildings have been systematically removed over time, or the buildings replaced with new structures, or adapted to different uses. The survival of the Kintore building, despite being partially damaged and robbed, might be due to the marginal nature of the ground it sits on, which is very boggy in places and contains a large amount of stone, both above and below ground, which inhibited ploughing that might otherwise have removed all traces of the building. Better preserved medieval buildings, such as at Pitcarmick in Perthshire, retain clear divisions between a living end containing a hearth, and byre end with a central drainage slot. No such internal arrangements were apparent at Kintore but soil micromorphology analysis of the soils within the building suggest that there were differences between floor deposits at either end. The west end was associated with domestic activities and the east end was richer in livestock dung, which may indicate the internal division of the house. While there was no central drain within the byre east end of the building, this lay at a lower level than the west end, with the slope aiding drainage if animals were housed there.

Better preserved medieval buildings, such as at Pitcarmick in Perthshire, retain clear divisions between a living end containing a hearth, and byre end with a central drainage slot. No such internal arrangements were apparent at Kintore but soil micromorphology analysis of the soils within the building suggest that there were differences between floor deposits at either end. The west end was associated with domestic activities and the east end was richer in livestock dung, which may indicate the internal division of the house. While there was no central drain within the byre east end of the building, this lay at a lower level than the west end, with the slope aiding drainage if animals were housed there.