Newly published archaeological research from excavations undertaken at the Udal in North Uist reveals some of the hardships of life in Neolithic and early Bronze Age Scotland. Two burial cairns held the remains of individuals dating to the second millennium BC. Scientific analyses of these individuals demonstrate the dramatic effect that environmental stresses had on the community.

Newly published archaeological research from excavations undertaken at the Udal in North Uist reveals some of the hardships of life in Neolithic and early Bronze Age Scotland. Two burial cairns held the remains of individuals dating to the second millennium BC. Scientific analyses of these individuals demonstrate the dramatic effect that environmental stresses had on the community.

Excavations at the Udal revealed the archaeological remains of two round buildings dating to between 3000 and 2500 BC. Analysis of the artefacts indicates that butchering of animals, pottery-making and quartz tool manufacture took place here.

‘The two houses may have been the last surviving structures of a larger settlement that was covered over by a thick layer of blown sand, like Skara Brae on Orkney,’ said Beverley Ballin Smith of GUARD Archaeology, who has been leading the post-excavation work. ‘The storm that brought the sand covered fields and grazing lands in addition to the village, from dunes to the west. The effects were so severe that the buildings and the farming land had to be abandoned and people moved inland. How long it took the sand to consolidate before it could be used for grazing and agriculture is not known, but marks from an ard plough showed that fields had extended much further west and north than the coastline does today.’

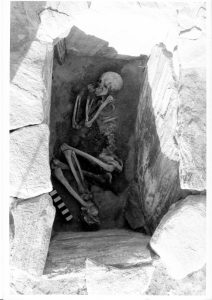

The blown sand was only part of the environmental story as another severe storm later brought a flood that destroyed the new fields by depositing a thick stone and shingle beach across them. By this time the coastal landscape was in flux and was in the process of being dramatically transformed. The archaeological evidence reveals that these environmental hardships had a severe effect on the health of local inhabitants. Scientific analysis of the teeth of two skeletons buried on the site indicated they had suffered a lack of food as children, even periods of starvation, and shell fish such as whelks may have become a staple food stuff.

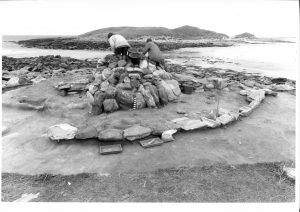

The accumulation of sand and the flooding episode separated the end of the late Neolithic settlement from the beginning of the early Bronze Age, around 2400 BC. Sometime after the creation of the beach, a burial cairn was built, under which a young man was laid to rest in stone cist. This large round mound of stone and turf was the largest man-made structure on the Udal peninsula. By erecting the cairn, the inhabitants that lived in the area claimed back the landscape as theirs. The monument was meant to be enduring and it lasted approximately 4000 years before coastal erosion threatened it, necessitating its excavation.

The accumulation of sand and the flooding episode separated the end of the late Neolithic settlement from the beginning of the early Bronze Age, around 2400 BC. Sometime after the creation of the beach, a burial cairn was built, under which a young man was laid to rest in stone cist. This large round mound of stone and turf was the largest man-made structure on the Udal peninsula. By erecting the cairn, the inhabitants that lived in the area claimed back the landscape as theirs. The monument was meant to be enduring and it lasted approximately 4000 years before coastal erosion threatened it, necessitating its excavation.

‘Our Neolithic and Bronze Age ancestors lived through climate change events such as dramatic sea-level rise and increased storminess, and trauma such as loss of fields, crops and animals. They had to relocate their settlement and houses to safer areas,’ said Beverley. ‘How the inhabitants of the Udal survived during the Bronze Age will be part of the research on the next Udal site – the South mound.’

‘Our Neolithic and Bronze Age ancestors lived through climate change events such as dramatic sea-level rise and increased storminess, and trauma such as loss of fields, crops and animals. They had to relocate their settlement and houses to safer areas,’ said Beverley. ‘How the inhabitants of the Udal survived during the Bronze Age will be part of the research on the next Udal site – the South mound.’

The Udal is a peninsula off the north coast of North Uist and was the focus of many years of archaeological excavations by the late Iain Crawford. This book is the result of several years of post-excavation work on the smallest of the Udal sites, which was exposed by coastal erosion after an exceptional high tide in 1974. While Iain Crawford completed the fieldwork by 1984 he could not complete the project to publication. After a long illness he died in 2016 at the age of 88. The new book is edited by Beverley Ballin Smith, Publications Manager at GUARD Archaeology, who has spent the last few years analysing the archaeological material recovered from Iain’s excavations.

‘While the archaeology of the Western Isles is as rich, diverse and intriguing as that of the rest of Scotland, it is less well known,’ said Malcolm Burr, Chief Executive of Comhairle nan Eilean Siar. ‘Comhairle nan Eilean Siar and its partners are working hard to see this position change, and this new publication of the smallest of Iain Crawford’s excavations at the Udal site in North Uist, is part of this effort. The excavations at the Udal recovered fragile evidence in the face of erosion by sea, storm and the ravages of time. The story told by these structures and artefacts, however, reflects the earliest centuries of communities’ life experiences on the Udal headland from some six thousand years ago, one of the longest and most fascinating time lines in the archaeology of Scotland. The two Neolithic houses and Bronze Age burial cairn bear testimony to the antiquity and importance of this site.’

Dr Lisa Brown from Historic Environment Scotland said ‘It is great to see these results of the excavation of the Neolithic and Bronze Age remains now published, both as a book and free to download online. Using the most up to date scientific techniques, the author and contributors have been able to provide additional insight into how the earliest communities were living on this peninsular, and how they coped with the changes in the environment which affected their lives. We are pleased to have been able to support this work through our archaeology funding programme.’

This first major publication from the Udal project was launched at Sollas Community Hall in North Uist and was jointly funded by Historic Environment Scotland and Comhairle nan Eilean Siar.

The new hardback book, Life on the Edge: The Neolithic and Bronze Age of Iain Crawford’s Udal, North Uist edited by Beverley Ballin Smith is available from Archaeopress Publishing Ltd, at www.archaeopress.com for £25. A free version is also available to download from the same internet address.