Category Archives: Blog

Reconstruction model

As part of the post-excavation work, we commissioned Jim Conquer to recreate the Neolithic and Bronze Age settlements at Carnoustie. Along with the replica artefacts from the Carnoustie Hoard, these will be given to Angus Alive for permanent display at a local venue.

Neolithic archaeobotanical remains

An important part of the post-excavation works was the analyses of carbonised archaeobotanical remains.

The charcoal assemblage from the larger Neolithic hall was overwhelmingly dominated by oak, which made up over 90% of the charcoal identified from this structure. When just the exterior post-hole fills are considered, oak forms 94% of the identified charcoal. The only other type of charcoal that has any significant representation in this structure was alder (7% of all charcoal). It is probable that at least some of this oak is the remains of structural timbers and that the hall was built from oak posts. This would correspond with the charcoal assemblages recovered from other Neolithic halls in Scotland, which have been suggested as destroyed by fire. If that also occurred at Carnoustie, then it may be that this hall did not have any significant amount of hazel wattle as walls or internal divisions as it would be expected that much more hazel charcoal would have been recorded from the structure if hazel had formed a significant part of the structure. It is also likely that oak was the main fuel source used in this Early Neolithic Hall. Oak was the dominant tree type present in lowland broadleaved woodland during the Neolithic and so would have been readily available for both building structures and burning in hearths.

While cereal grains were not abundant in the larger Neolithic Hall, naked barley, emmer wheat and bread wheat were all represented. Naked barley, often with emmer wheat, is strongly associated with Neolithic sites in Scotland. The combination of emmer wheat, bread wheat and barley is also recorded from other Neolithic timber halls in Scotland. Bread wheat is very rare in the Scottish prehistoric archaeobotanical record but is abundant in Germany and Denmark during this period. It would seem that bread wheat was not commonly grown or eaten during the Neolithic in Scotland but its presence in features from Neolithic timber halls suggests that it may be associated with the status and function of these particular types of structures. There is no evidence for crop weeds or crop processing waste in any of the samples and so this might indicate that only fully cleaned grain was being brought into the structure. The only other evidence for food plant remains from the larger Neolithic Hall at Carnoustie were carbonised hazel nutshell fragments and a few apple pips. Hazelnuts were a readily available food resource but apple pips are very rare in the Scottish archaeobotanical record.

The archaeobotanical evidence indicates that the smaller Neolithic hall at Carnoustie was built from oak but, again, there is little evidence for any substantial use of hazel wattle in the structure. The main difference between the carbonised assemblages is that there were over 8 times as many cereal grains in the smaller Neolithic hall than the larger. 35% of the cereal grains were identifiable as barley with 12% identifiable as naked barley. The remaining grains were wheat, with a few further identifiable as emmer wheat but no bread wheat was found in this structure. No crop weeds or chaff were identified either.

The pottery vessels from Carnoustie

The earliest domestic pottery vessels found on the Carnoustie site are early Neolithic carinated (shouldered) bowls from c. 5500 years ago. They have curled over rims, and shoulders which divide the rim and neck from the belly and the rounded base. No complete pot survived but fragments tell us that some were finished with smoothed and polished (burnished) surfaces, while others had deliberate finger rilling (dragging the fingers down the neck of the vessel) to form a textured pattern. Occasional holes, perhaps three to four piercing the pottery around the vessel below the rim show that some vessels were suspended over the fire rather than placed in the ashes of the hearth. Many of these pots were used for food preparation.

Later Neolithic potters developed different shapes of vessels with simple rims, and decorated them with designs that were pressed into the clay – middle to late Neolithic Impressed Wares. The ends of twigs, bird bones, perhaps a flint blade, finger tips and finger nails were common tools used in decoration. The neck of vessels below the rim were decorated with designs that were horizontal, but lower down the pot the designs are more random. On some vessels, designs were created using bone and twigs, or fingernail and twig/blade, as in this example and the one above.

By the end of the Neolithic and the beginning of the Bronze Age, 4500 years ago, the function of some pottery vessels changed and although pots continued to be used for domestic purposes, some were produced to hold the cremated remains of the dead. An almost complete Beaker vessel was reconstructed. Its horizontal design was made by a wool cord wound round the whole vessel and impressed into the clay. Another pot, a funerary urn had been distorted and broken in the pit in which it lay. Note below the row of finger tip impressions decorating the pot below the rim.

A Bronze Age village & more

A clutch of radiocarbon dates ranging between around 1200 BC to 900 BC, were recovered from the structures clustered to the north-east of the Neolithic hall. This is where the pit containing the Late Bronze Age hoard (dated to 1118-924 BC) was found. Which indicates that the hoard was buried in the middle of a large contemporary settlement. Five circular or sub-circular houses were revealed during the excavation, from which these radiocarbon dates were extracted, though as these were found right at the eastern limit of the excavation, this village undoubtedly extended beyond (underneath the road leading to Carnoustie High School). So we have a remarkable archaeological context for the hoard. Analyses of the artefacts and ecofacts from this settlement will provide information about the lifestyle of the people who buried the hoard.

But that’s not all!

Because the radiocarbon dates also revealed that the site was occupied sometime between around 700 to 1000 AD during the early medieval period. These dates came from features across the central eastern part of the site and while the only structure that we can just now confidently date to this period is a curious linear stone structure which yielded a radiocarbon date of 769-888 AD; this evidence clearly demonstrates that there was a Pictish settlement here too. Which was not expected!

More reveals from radiocarbon dates

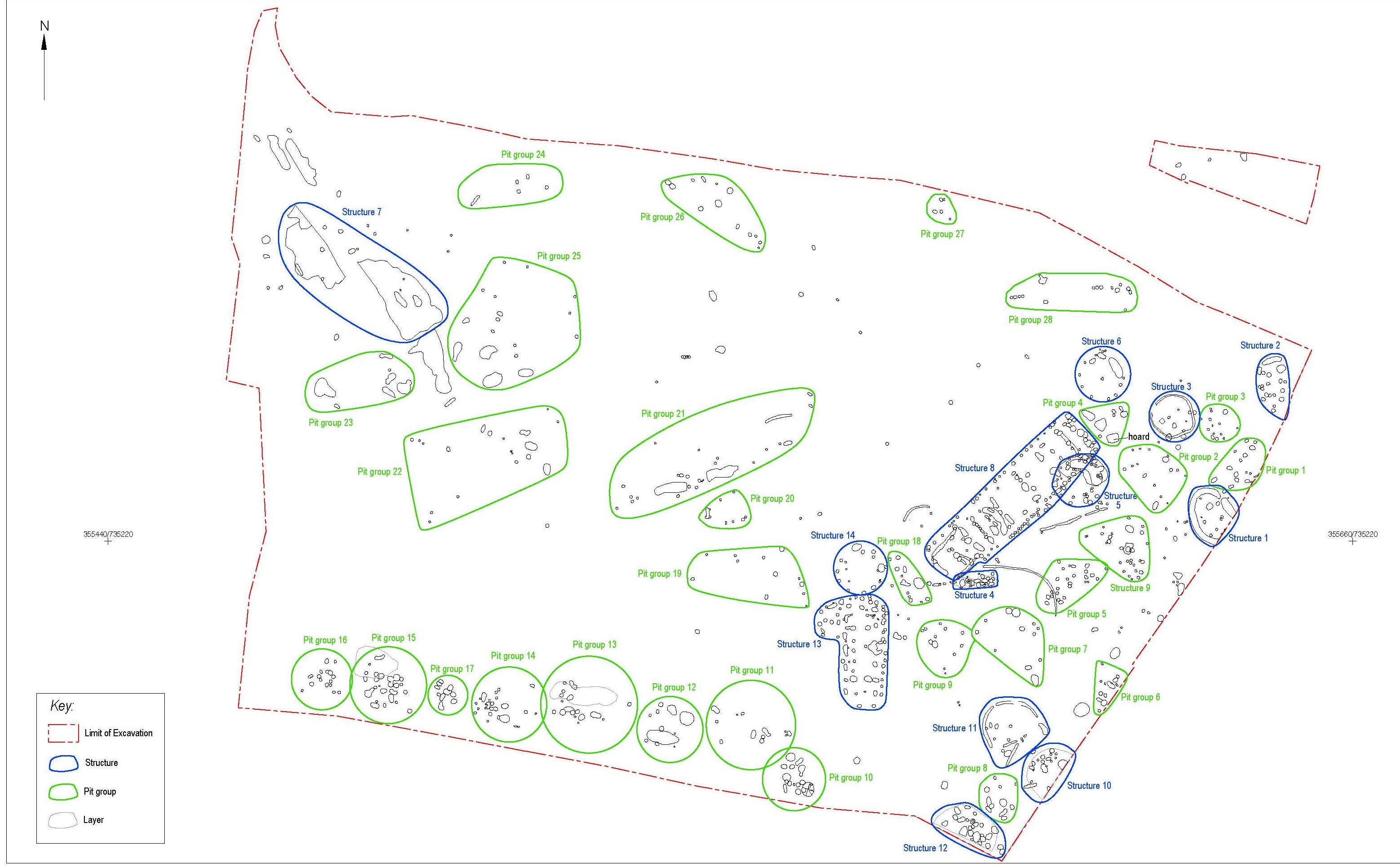

So now that we have radiocarbon dating evidence for Early-Mid Neolithic occupation of the larger rectilinear hall (Structure 8) at Carnoustie, what does the latest batch of radiocarbon dates tell us about the context of this settlement?

The other large rectilinear hall (Structure 13) which lies just to the south-west of the larger hall has yielded calibrated radiocarbon dates ranging between 3938-3033 BC, which indicates that it was contemporary with the larger hall and may even have carried on after the larger hall was abandoned.

But perhaps the most surprising aspect to be revealed by the latest batch of radiocarbon dates is that many of the other features have yielded Neolithic dates too. These include structures 10 and 12 that extend beyond the southern corner of the site and the numerous groups of pits that lie to the east and south west of the two Neolithic halls, which have produced calibrated radiocarbon dates from across the fourth millennium BC. So it is clear that the two Neolithic halls lay within a much bigger settlement area.

What’s also apparent from the radiocarbon dates is that the Late Bronze Age settlement contemporary with the hoard lay clustered in that part of the site north-east of the larger hall. But more about this later…

Radiocarbon dating the larger Neolithic Hall

Aerial shot of Neolithic hall (from west)

So far, we have received three radiocarbon dates from the larger Neolithic hall (Structure 8) at Carnoustie. Three of the post-holes at the north-eastern gable end of the hall have yielded calibrated (2 sigma) dates from single entity samples (willow, alder and hazel) of 3694-3530 BC, 3929-3703 BC and 3893-3653 BC. Which confirms our assumption that this was an Early Neolithic structure of the early fourth millennium BC.

Those dates are really close to the radiocarbon dates recovered from other Neolithic halls in Scotland such as Balbridie in Aberdeenshire and Doon Hill in East Lothian. So it’ll be interesting to see whether the smaller building (Structure 13) at Carnoustie, which lies on different alignment south of the larger hall, yields a different range of radiocarbon dates.

What radiocarbon dates are beginning to tell us

The first batch of radiocarbon dates have come back with some interesting results. First of all a couple of occupation layers within Structure 5 (a roundhouse just to the south of the pit containing the Late Bronze Age hoard) have yielded calibrated radiocarbon dates of 1118-931 BC and 1082-905 BC. These dates are very close if not pretty much identical to the calibrated radiocarbon date of 1118-924 BC obtained from the wooden scabbard of the Carnoustie sword. So this confirms that the hoard was buried within a pit that lay within a contemporary Late Bronze Age settlement.

Carnoustie excavation plan

Another question is whether this settlement just comprised the one roundhouse or whether at least some of the other apparent buildings and houses were contemporary with this. Well, another building, Structure 1, which is elliptical in shape and lies to just to the east of Structure 5, yielded calibrated radiocarbon dates of 1046-916 BC and 920-818 BC. Structure 2, a sub-circular structure to the north of Structure 1, yielded calibrated radiocarbon dates of 1084-912 BC and 1192-998 BC. Structure 3, another roundhouse which lies just to the east of the hoard pit yielded a calibrated radiocarbon date of 1207-1017 BC.

Altogether, these radiocarbon dates provide a context for the burial of the Carnoustie hoard. The dates suggest that the hoard was buried within a pit that lay within a large settlement that had developed over the course of the last couple of centuries of the second millennium BC and on into the first couple of centuries of the first millennium BC – ie the Late Bronze Age.

Which is very exciting. And we haven’t yet mentioned the radiocarbon dates for the earlier Neolithic Hall!

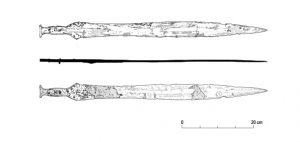

Replica Bronze Age sword and spearhead

Although the museum where the excavation assemblage will be eventually exhibited has yet to be determined, Angus Council are keen to be proactive in the presentation of these important finds within the Angus area. To this end the programme of post-excavation works includes the production of replica items from the Bronze Age Carnoustie hoard discovered at the site, which will be suitable for public display and educational purposes. It will be possible for all items to be handled by children and adults, under supervision.

Although the museum where the excavation assemblage will be eventually exhibited has yet to be determined, Angus Council are keen to be proactive in the presentation of these important finds within the Angus area. To this end the programme of post-excavation works includes the production of replica items from the Bronze Age Carnoustie hoard discovered at the site, which will be suitable for public display and educational purposes. It will be possible for all items to be handled by children and adults, under supervision.

The replica spearhead, sword and pin were cast and finished at a scale of 1:1 by Neil Burridge, a Bronze Age metalwork expert who has provided similar items for display and reenactment purposes across Britain for over 12 years (http://www.bronze-age-swords.com). Neil also produced a scabbard for the sword.

The replica spearhead, sword and pin were cast and finished at a scale of 1:1 by Neil Burridge, a Bronze Age metalwork expert who has provided similar items for display and reenactment purposes across Britain for over 12 years (http://www.bronze-age-swords.com). Neil also produced a scabbard for the sword.

Neil was provided with scale illustrations of the sword and spear prepared by GUARD Archaeology’s Senior Graphic Officer, Gillian Sneddon. This ensured that the replica objects are an accurate representation of the items discovered at Carnoustie. The items were cast in bronze, and the sword hilted in a similar material to that found in the hoard. The golden collar on the spearhead was replicated in design and form with a gold coloured base metal.

Neil was provided with scale illustrations of the sword and spear prepared by GUARD Archaeology’s Senior Graphic Officer, Gillian Sneddon. This ensured that the replica objects are an accurate representation of the items discovered at Carnoustie. The items were cast in bronze, and the sword hilted in a similar material to that found in the hoard. The golden collar on the spearhead was replicated in design and form with a gold coloured base metal.

Late Bronze Age bangle fragment

Carnoustie Late Bronze Age Bangle

This fragment of a cannel coal or shale bangle is an example of a Late Bronze Age item of jewellery that was comparatively rare in Scotland and which could well be contemporary with the hoard of metalwork found just around 5 m away. The recurrent association of such bangles with other valuable items including metalwork suggests that they formed part of the ‘vocabulary of esteem’ among the elite of Late Bronze Age society.

‘Its size suggests that it had been an adult’s,’ said Alison Sheridan, from National Museums Scotland, who analysed the bangle. ‘The discovery of such a bangle in a domestic context in northern Britain, datable from the roundhouse in which the pit was located, represents a welcome addition both to the contextual range of find spots and to the chronological evidence for the use of this type of object during the Late Bronze Age.’

Fragment of cannel coal or shale bangle from Carnoustie

It is hard to tell whether locally-available cannel coal or oil shale had been used to manufacture this bangle, since sourcing these particular materials requires sampling of the object. However, there are abundant supplies of cannel coal in the coalfield deposits of Fife, and shale is also available within a few kilometres of Carnoustie, so in theory this need not have been an exotic import. While Late Bronze Age bangles are likely to have been made by specialists, the scale of production in northern Britain may not have been large, to judge from their rarity.

As for how the bangle had been made, there are two basic methods: the first involves pecking or gouging a hole in the centre of a roughout then expanding the hole by cutting, and the second involves cutting a disc from the centre, leaving a disc-shaped waster or ‘core’, usually with a bevelled edge (from where the disc had been cut from either side of the roughout). The latter technique, rare in Scotland, is characteristic of Iron Age and early medieval bangles, and no pre-Iron Age example of a disc-shaped waster is known. This suggests that the Carnoustie bangle had probably been made by expanding a small central hole; the cut-marks running around the interior of the hoop are consistent with this.