In January 2018, the specialist post-excavation analyses of the Carnoustie hoard was collated into a report by Alison Sheridan. This revealed that the sword had been wrapped in a woolen blanket or cloak when it was buried. The leaf-shaped bronze sword is classed as a Ewart Park type. Radiocarbon dates for Ewart Park phase metalwork in Scotland are sparse; the Carnoustie date of around 1000 BC is valuable new knowledge, which extends this phase of metalwork backwards in time than the 900–800 BC date bracket usually attributed for Ewart Park metalwork.

In January 2018, the specialist post-excavation analyses of the Carnoustie hoard was collated into a report by Alison Sheridan. This revealed that the sword had been wrapped in a woolen blanket or cloak when it was buried. The leaf-shaped bronze sword is classed as a Ewart Park type. Radiocarbon dates for Ewart Park phase metalwork in Scotland are sparse; the Carnoustie date of around 1000 BC is valuable new knowledge, which extends this phase of metalwork backwards in time than the 900–800 BC date bracket usually attributed for Ewart Park metalwork.

The spearhead had been wrapped in sheepskin when it was buried with the sword. The leaf-shaped bronze spearhead is of Type 11A in the latest typology of British Late Bronze Age spearheads and is among the longest examples of its type. There were no traces of wood (from a shaft) in its socket. Compositional analysis of the bronze of the spearhead, undertaken by Peter Northover, revealed that it comprises 86.7% copper, 11.4% tin and 0.68% lead, with trace amounts of several other elements. Lead isotope analysis by Jane Evans and Vanessa Pashley of the Natural Environment Research Council revealed that the lead probably originated in a central English ore field. Compositional analysis of the gold by Lore Troalen from National Museums Scotland revealed the gold to be of high purity, and lead isotope analysis of the gold showed that it grouped with southern Irish and southern British ore compositions. An origin of the lead content in an English ore field seems likely.

The spearhead had been wrapped in sheepskin when it was buried with the sword. The leaf-shaped bronze spearhead is of Type 11A in the latest typology of British Late Bronze Age spearheads and is among the longest examples of its type. There were no traces of wood (from a shaft) in its socket. Compositional analysis of the bronze of the spearhead, undertaken by Peter Northover, revealed that it comprises 86.7% copper, 11.4% tin and 0.68% lead, with trace amounts of several other elements. Lead isotope analysis by Jane Evans and Vanessa Pashley of the Natural Environment Research Council revealed that the lead probably originated in a central English ore field. Compositional analysis of the gold by Lore Troalen from National Museums Scotland revealed the gold to be of high purity, and lead isotope analysis of the gold showed that it grouped with southern Irish and southern British ore compositions. An origin of the lead content in an English ore field seems likely.

The Carnoustie spearhead is one of only five examples of spearheads adorned with gold binding in Britain and Ireland, the others being from Pyotdykes near Dundee, Harrogate in Yorkshire, Lough Gur in County Limerick in south-west Ireland and another from Ireland.

The Carnoustie spearhead is one of only five examples of spearheads adorned with gold binding in Britain and Ireland, the others being from Pyotdykes near Dundee, Harrogate in Yorkshire, Lough Gur in County Limerick in south-west Ireland and another from Ireland.

A complete but fragmented bronze sunflower-headed, swan’s neck bronze pin was found lying over the pommel, hilt and upper blade area of the sword, its head at the pommel end. Fragments of woven textile were associated with this pin, including in the narrow area between the shank and the back of the pinhead – thereby indicating that the pin had been used to securing the woolen cloth wrapped around the sword. Compositional analysis using X-ray fluorescence revealed that the pin, like the sword and the spearhead, is of leaded bronze.

A complete but fragmented bronze sunflower-headed, swan’s neck bronze pin was found lying over the pommel, hilt and upper blade area of the sword, its head at the pommel end. Fragments of woven textile were associated with this pin, including in the narrow area between the shank and the back of the pinhead – thereby indicating that the pin had been used to securing the woolen cloth wrapped around the sword. Compositional analysis using X-ray fluorescence revealed that the pin, like the sword and the spearhead, is of leaded bronze.

The fragments of textile were examined by Susanna Harris of the University of Glasgow using scanning electron microscopy, who concluded that all were of sheep’s wool, and that at least two different textiles were represented. One, found around the socket of the spearhead is a fine, tabby weave, woven using z-spun thread with one thread system finer that the other. The other, found associated with the pin and the annular mount that decorated the scabbard, is a slightly coarser fabric, woven with z-spun yarns with thread systems of similar diameter. There is no sign of any dye in either fabric.

The fragments of textile were examined by Susanna Harris of the University of Glasgow using scanning electron microscopy, who concluded that all were of sheep’s wool, and that at least two different textiles were represented. One, found around the socket of the spearhead is a fine, tabby weave, woven using z-spun thread with one thread system finer that the other. The other, found associated with the pin and the annular mount that decorated the scabbard, is a slightly coarser fabric, woven with z-spun yarns with thread systems of similar diameter. There is no sign of any dye in either fabric.

The fact that a very similar deposit was found at Pyotdykes, just 20 km to the west of Carnoustie is remarkable. Along with numerous other finds of Late Bronze Age metalwork in Tayside and Fife, this attests to the wealth of the Late Bronze Age elite in this part of Scotland. The Pyotdykes deposit comprised two swords (with traces of a composite wood and animal skin scabbard associated with one) and a gold-bound spearhead.

During the Artefacts Illustration workshop, the students were shown a selection of finds from Carnoustie (prehistoric stone tools, lithics and pottery) and were then asked to select one that they would like to draw. They then learned how to draw different types of artefacts by drawing around it then using dividers to measure and correct the outline. They also used a magnifier to add in detail and were given a small light to create a light source for shading. Once they had finished the pencil drawing they traced over it using fibre tipped pens to produce a final drawing.

During the Artefacts Illustration workshop, the students were shown a selection of finds from Carnoustie (prehistoric stone tools, lithics and pottery) and were then asked to select one that they would like to draw. They then learned how to draw different types of artefacts by drawing around it then using dividers to measure and correct the outline. They also used a magnifier to add in detail and were given a small light to create a light source for shading. Once they had finished the pencil drawing they traced over it using fibre tipped pens to produce a final drawing. For the Artefacts Photography workshop, t

For the Artefacts Photography workshop, t 602 lithic artefacts were recovered from the Carnoustie excavation and subjected to analysis by Torben Ballin. He found out that the lithics mainly comprise flint and quartz but with some pitchstone and quartzite. About 92% of this assemblage is waste material produced in the making of prehistoric stone implements. The remaining 8% of the lithic artefacts are actual tools such as arrowheads, knives and scrapers.

602 lithic artefacts were recovered from the Carnoustie excavation and subjected to analysis by Torben Ballin. He found out that the lithics mainly comprise flint and quartz but with some pitchstone and quartzite. About 92% of this assemblage is waste material produced in the making of prehistoric stone implements. The remaining 8% of the lithic artefacts are actual tools such as arrowheads, knives and scrapers. In March 2018, the final programme of post-excavation analyses of the archaeological remains at Carnoustie got underway with the wet-sieving of the soil samples taken during the excavation. This is the process by which we recover tiny minute environmental evidence (such as charred cereal grains) which might reveal the diet of the people who inhabited the site at Carnoustie during the Neolithic and Bronze Age.

In March 2018, the final programme of post-excavation analyses of the archaeological remains at Carnoustie got underway with the wet-sieving of the soil samples taken during the excavation. This is the process by which we recover tiny minute environmental evidence (such as charred cereal grains) which might reveal the diet of the people who inhabited the site at Carnoustie during the Neolithic and Bronze Age. In January 2018, the specialist post-excavation analyses of the Carnoustie hoard was collated into a

In January 2018, the specialist post-excavation analyses of the Carnoustie hoard was collated into a  The spearhead had been wrapped in sheepskin when it was buried with the sword.

The spearhead had been wrapped in sheepskin when it was buried with the sword.  The Carnoustie spearhead is one of only five examples of spearheads adorned with gold binding in Britain and Ireland, the others being from Pyotdykes near Dundee, Harrogate in Yorkshire, Lough Gur in County Limerick in south-west Ireland and another from Ireland.

The Carnoustie spearhead is one of only five examples of spearheads adorned with gold binding in Britain and Ireland, the others being from Pyotdykes near Dundee, Harrogate in Yorkshire, Lough Gur in County Limerick in south-west Ireland and another from Ireland. A complete but fragmented bronze sunflower-headed, swan’s neck bronze pin was found lying over the pommel, hilt and upper blade area of the sword, its head at the pommel end. Fragments of woven textile were associated with this pin, including in the narrow area between the shank and the back of the pinhead – thereby indicating that the pin had been used to securing the woolen cloth wrapped around the sword. Compositional analysis using X-ray fluorescence revealed that the pin, like the sword and the spearhead, is of leaded bronze.

A complete but fragmented bronze sunflower-headed, swan’s neck bronze pin was found lying over the pommel, hilt and upper blade area of the sword, its head at the pommel end. Fragments of woven textile were associated with this pin, including in the narrow area between the shank and the back of the pinhead – thereby indicating that the pin had been used to securing the woolen cloth wrapped around the sword. Compositional analysis using X-ray fluorescence revealed that the pin, like the sword and the spearhead, is of leaded bronze. The fragments of textile were examined by Susanna Harris of the University of Glasgow using scanning electron microscopy, who concluded that all were of sheep’s wool, and that at least two different textiles were represented. One, found around the socket of the spearhead is a fine, tabby weave, woven using z-spun thread with one thread system finer that the other. The other, found associated with the pin and the annular mount that decorated the scabbard, is a slightly coarser fabric, woven with z-spun yarns with thread systems of similar diameter. There is no sign of any dye in either fabric.

The fragments of textile were examined by Susanna Harris of the University of Glasgow using scanning electron microscopy, who concluded that all were of sheep’s wool, and that at least two different textiles were represented. One, found around the socket of the spearhead is a fine, tabby weave, woven using z-spun thread with one thread system finer that the other. The other, found associated with the pin and the annular mount that decorated the scabbard, is a slightly coarser fabric, woven with z-spun yarns with thread systems of similar diameter. There is no sign of any dye in either fabric. One of the key questions we had was: precisely how old was the Carnoustie hoard? This is where the wooden scabbard (identified

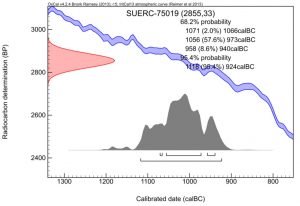

One of the key questions we had was: precisely how old was the Carnoustie hoard? This is where the wooden scabbard (identified  In September 2017, we received the radiocarbon date for the wooden scabbard from the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre in East Kilbride. The radiocarbon dating revealed a 95.4% that the scabbard dated to between 1118 BC and 924 BC. This is very significant new evidence because it not only dates the burying of the hoard to around 1000 BC but is one of the few direct scientific dates for such Late Bronze Age metalwork in Britain (because most of such metalwork has no organic remains that can be radiocarbon dated).

In September 2017, we received the radiocarbon date for the wooden scabbard from the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre in East Kilbride. The radiocarbon dating revealed a 95.4% that the scabbard dated to between 1118 BC and 924 BC. This is very significant new evidence because it not only dates the burying of the hoard to around 1000 BC but is one of the few direct scientific dates for such Late Bronze Age metalwork in Britain (because most of such metalwork has no organic remains that can be radiocarbon dated).

On 17 February 2017, the GUARD Archaeology team completed their excavation of the archaeological remains at Balmachie Road, Carnoustie. Altogether they had recorded the remains of up to 12 sub-circular houses that probably date to the Bronze Age along with the remains of two rectilinear halls that likely date to the Neolithic period. The Neolithic features are significant in themselves, and include the largest Neolithic Hall ever found in Scotland. The hoard was buried in a pit close to a roundhouse that cut through the large Neolithic hall.

On 17 February 2017, the GUARD Archaeology team completed their excavation of the archaeological remains at Balmachie Road, Carnoustie. Altogether they had recorded the remains of up to 12 sub-circular houses that probably date to the Bronze Age along with the remains of two rectilinear halls that likely date to the Neolithic period. The Neolithic features are significant in themselves, and include the largest Neolithic Hall ever found in Scotland. The hoard was buried in a pit close to a roundhouse that cut through the large Neolithic hall. Over the

Over the  Normally post-excavation analyses of artefacts recovered from excavations only begins once the entire excavation has been completed. But in the case of the Carnoustie hoard, specialist analyses was required as soon as possible. This was because the organic remains within the hoard were so delicate and fragile that there was a danger that they would degrade within a very short time. They urgently needed conservation but before this could take place, specialists required to examine the remains and take appropriate samples for scientific testing (such as radiocarbon dating, isotope analyses, X-ray Fluorescence analyses) to extract crucial information about the artefacts.

Normally post-excavation analyses of artefacts recovered from excavations only begins once the entire excavation has been completed. But in the case of the Carnoustie hoard, specialist analyses was required as soon as possible. This was because the organic remains within the hoard were so delicate and fragile that there was a danger that they would degrade within a very short time. They urgently needed conservation but before this could take place, specialists required to examine the remains and take appropriate samples for scientific testing (such as radiocarbon dating, isotope analyses, X-ray Fluorescence analyses) to extract crucial information about the artefacts. So post-excavation analyses of the hoard begins in January 2017 with a

So post-excavation analyses of the hoard begins in January 2017 with a