Archaeological investigations undertaken in the north of Scotland by GUARD Archaeology, which sheds new light on bloomery iron working tradition between the late 15th–early 17th centuries, has just been published in the latest volume of the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

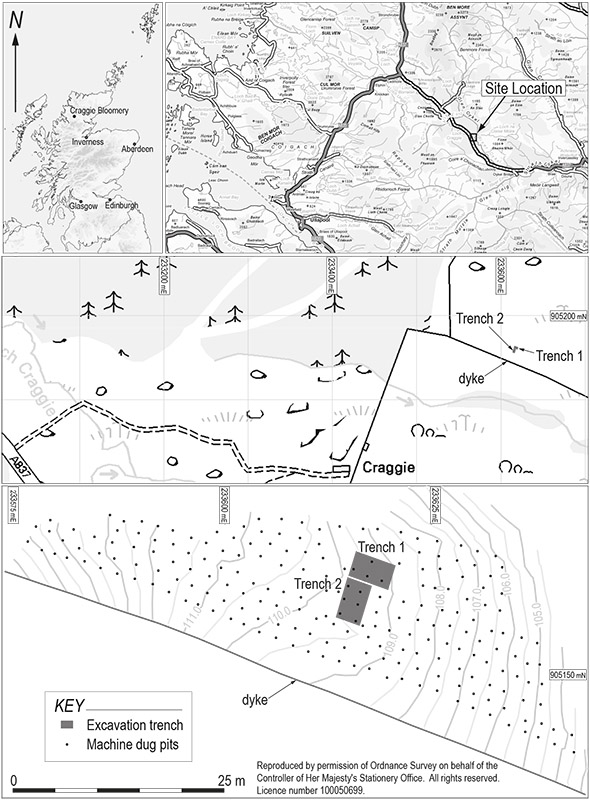

Over a long weekend in mid-September 2010, volunteers from North of Scotland Archaeology Service and John Atkinson of GUARD Archaeology discovered and excavated a late medieval bloomery on a terrace to the north-east of Craggie Cottage in Glen Oykel in Sutherland.

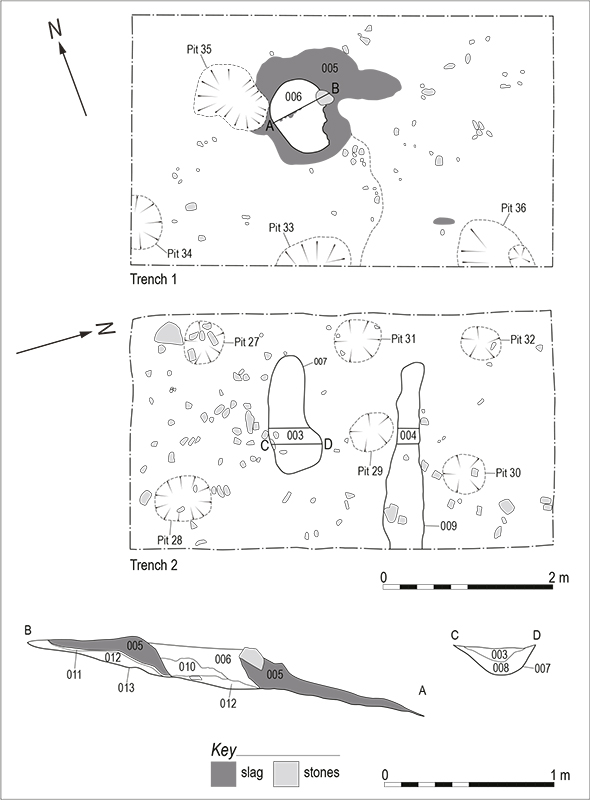

The excavation revealed the remains of an oval furnace bowl founded upon an old ground surface constructed mainly of friable slag material, which sat over a thin band of heat-affected red clay, it had a profile that included a distinct overhang along the eastern interior. No visible sign of a tuyere hole was evident but the most likely position for this and the associated bellows was on the higher ground to the west. The bowl contained traces of the final firing in the form of a charcoal and slag-rich layer. Analysis of the charcoal revealed that birch dominated the fill, with small traces of alder present. A sample of birch round wood was selected for dating and returned a date range of cal AD 1470–1650. A further discrete sample of birch charcoal was also recovered from beneath the furnace bowl and returned a range of cal AD 1490–1670.

‘The assemblage of industrial waste from Craggie is typical of bloomery smelting sites,’ said Christine Rennie, who analysed the iron working waste. ‘Much of the material collected was classified as furnace lining, however, at least a third of the assemblage was constituted by iron working waste and occasional fragments of tap slag. The low occurrence of tap slag is unusual for a bloomery site.’

‘The domination of birch charcoal is unusual for a bloomery, but may reflect utilisation of abundantly available local resources,’ added Jennifer Miller, who examined the botanical remains. ‘The high tar content of birch generates a large volume of sticky soot on burning and it is possible that this was a contributing factor to the clay furnace becoming dominated by iron waste products.’

‘Craggie is notable as a rare example of a previously unrecorded bloomery scatter and especially important given the identification and excavation of a furnace at the site,’ said Project Director John Atkinson. ‘It is also exceptional in terms of its scale and construction. The furnace is substantially larger than comparable examples previously excavated in Argyll.’

In dating terms, Craggie sits within the known sequence for bloomery sites in late medieval Scotland, which date broadly from the 13th to 17th centuries. The corroborative dating evidence from Craggie, together with the unusual scale and design of the furnace, its friable slag-rich walls and absence of a slag mound may all point to its use having been limited to a short period. What does seem likely is that the furnace produced the classic ‘toffee-like’ slag normally associated with functioning bloomery furnaces, and there is clear evidence – in the volume of material recovered (including waste and furnace lining) – to suggest that it operated on more than one occasion. The lack of hammer scale within any of the adjacent features implies that its prime function was related more to smelting than smithing. The presence of birch within the last firing and the evidence of its high tar content may explain why the furnace was abandoned so quickly.

As there are only 12 possible bloomery sites known from the whole of Sutherland, none of which have attracted any excavation, Craggie is unique in casting light upon an aspect of late medieval society in the Highlands that is rarely exposed to scrutiny.

GUARD Archaeology is extremely grateful to Forestry Commission Scotland for funding the excavation, post-excavation and publication of this work. The full results of the excavation can be found in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (Volume 145).