Newly published GUARD Archaeology research into the harbour of Cambuskenneth Abbey near Stirling reveals a surprisingly intact medieval stone-built structure on the edge of the Forth along with a significant assemblage of medieval pottery, metalwork and other materials.

In September 2015, GUARD Archaeologist Warren Bailie led community archaeological investigations coinciding with the Inner Forth Festival, Door’s Open Day and Scottish Archaeology Month. Guided by GUARD Archaeology, community volunteers undertook a geophysical survey, hand-excavations, metal-detecting, planning, recording and finds processing. In addition, an independent metal-detecting survey was also conducted by the Scottish Artefact Recovery Group on the Abbot’s Ford, of which a summary of the results is included in this report. Primary school children from St Modan’s, St Ninians and Riverside schools took part in the investigations, as did students from the Scottish Agricultural College. The work was undertaken on behalf of Stirling Council and the Inner Forth Landscape Initiative, with funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund.

View of the Carse from Stirling Castle battlements

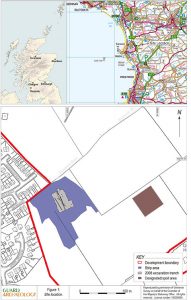

Cambuskenneth Abbey is situated on the low-lying flood plain or carse of the River Forth, some 1.5 km to the east of Stirling Castle. The abbey is located within a looping meander of the river creating a holm-like setting, on the north bank of the river, a location that gives it some degree of natural protection/isolation as the river flows by on three sides. The main points of access onto the meander, and therefore into the Abbey, do not appear to have been via dry land across the northern neck of the meanders, but via ferries across the western and eastern loop of the river, and a fording point also to the east of the Abbey. Evidence for a link between the western crossing and the Abbey takes the form of an E/W running trackway terminating at the river some 235 m to the west of the Abbey.

A prospect of Stirling from Cambuskenneth Abbey by John Slezer, 1693. Reproduced by permission of the Stirling Smith Art Gallery and Museum

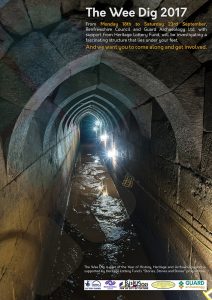

This part of the river has remained relatively unchanged since probably the later medieval period. The pottery provided a date range from the medieval period and provides a good indication of the type of pottery available. This comprised Scottish post-Medieval Reduced Ware pottery sherds, dating from the late fifteenth to eighteenth centuries, and Scottish Medieval Redware sherds, dating to thirteenth – fifteenth centuries. A fragment of a medieval horseshoe was also recovered from construction layers below two parts of the stepped harbour. None of the in situ built remains were removed during the investigations with only loose masonry material removed, and any apparent deposits were investigated through a series of hand excavated sections. The earliest foundation of the watergate and harbour could therefore potentially be earlier than the material recovered on this occasion suggests.

The medieval harbour along the upper river bank

The evidence from the topographical survey during these investigations suggested that the harbour could not feasibly function using the current mean tide levels. This indicates that the mean levels would have needed to be up to 2 m to 3 m higher than they are today in order for the harbour to be viable. The river level therefore must have changed considerably in recent centuries. Given that the watergate is shown in ruins in Slezer’s engraving of 1697, the harbour may have already been abandoned before this time, especially considering that the Abbey no longer functioned after 1559.

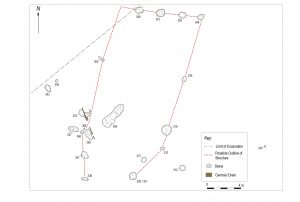

There are obvious above ground undulations identifying two banks/ditches leading in a slight curve from east to west, and these features probably at one time stretched between the east and west river banks, effectively closing off Cambuskenneth from the north. They are likely to have marked the outer precinct of the Abbey, although each may originate from different periods in the Abbey’s history. On Joan Blaeu’s Map of 1654, at least one palisade is shown around the landward side of Cambuskenneth Abbey. It should be noted that Blaeu’s maps were largely based on Timothy Pont’s work of the mid to late sixteenth century, which explains why Blaeu shows Cambuskenneth Abbey intact almost a century after the Reformation. The two curving features in the landscape later became used for a foot track (southern feature) and a carriage track (northern feature), both of which are annotated on the mid-nineteenth century deeds of Hood Farm, (which were kindly shown to the author by Mr Andrew Rennie, current tenant farmer). A pier and ferrying service are also shown leading north and eastwards across and along the Forth River at this point. A pin from a medieval brooch or buckle was recovered from the investigations in this area.

View of the track leading to the harbour. Stirling Castle lies on the horizon to the right.

The watergate and harbour served a number of purposes. They would have afforded the Abbey a degree of control over access to the site from the river and it was probably the point where the Abbey received much of its supplies by boat. In a phenomenological sense, the watergate also lay along the E/W sightline between Stirling Castle and Cambuskenneth Abbey, and therefore between these two iconic sites of power in the Medieval period. There is also reference to several monarchs visiting the Abbey, including Edward I and Robert the Bruce, who held his first parliament there in November 1314 after his battlefield victory over Edward II. The Abbey, and therefore its watergate and harbour, played an important role in Stirling’s history.

The full results of this research, ARO25: Abbots, Kings and Lost Harbours: Looking for Cambuskenneth’s Watergate, Stirling by Warren Bailie has just been published and is now freely available to download from the ARO website – Archaeology Reports Online.

Up until this time, during the earlier Mesolithic period (c. 8000-4000 BC), Scotland was inhabited by small groups of hunter gatherers, who led a nomadic lifestyle living off the land. The individuals that built this Neolithic house were some of the earliest communities in Ayrshire to adopt a sedentary lifestyle, clearing areas of forest to establish farms, growing crops such as wheat and barley and raising livestock such as cattle, sheep, goats and pigs.

Up until this time, during the earlier Mesolithic period (c. 8000-4000 BC), Scotland was inhabited by small groups of hunter gatherers, who led a nomadic lifestyle living off the land. The individuals that built this Neolithic house were some of the earliest communities in Ayrshire to adopt a sedentary lifestyle, clearing areas of forest to establish farms, growing crops such as wheat and barley and raising livestock such as cattle, sheep, goats and pigs.

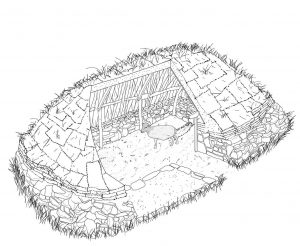

Newly published research by GUARD Archaeology has revealed the complex history of a turf and stone-built medieval building. Sherds of pottery obtained from the floor of the structure suggest it was in use during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries AD. However, its construction is similar to other excavated buildings dated to the early medieval period. Radiocarbon dates obtained from several features and deposits ranged from the Bronze Age, through the Iron Age to the medieval period. The structure is an uncommon survivor of medieval rural settlement that is rarely excavated in Scottish archaeology.

Newly published research by GUARD Archaeology has revealed the complex history of a turf and stone-built medieval building. Sherds of pottery obtained from the floor of the structure suggest it was in use during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries AD. However, its construction is similar to other excavated buildings dated to the early medieval period. Radiocarbon dates obtained from several features and deposits ranged from the Bronze Age, through the Iron Age to the medieval period. The structure is an uncommon survivor of medieval rural settlement that is rarely excavated in Scottish archaeology. The rareness of the Kintore medieval building is predominantly due to the lack of identification of them in the landscape, the result of their construction using perishable materials such as clay and turf, and changes in land-use which have led to their destruction. Often the stones from these buildings have been systematically removed over time, or the buildings replaced with new structures, or adapted to different uses. The survival of the Kintore building, despite being partially damaged and robbed, might be due to the marginal nature of the ground it sits on, which is very boggy in places and contains a large amount of stone, both above and below ground, which inhibited ploughing that might otherwise have removed all traces of the building.

The rareness of the Kintore medieval building is predominantly due to the lack of identification of them in the landscape, the result of their construction using perishable materials such as clay and turf, and changes in land-use which have led to their destruction. Often the stones from these buildings have been systematically removed over time, or the buildings replaced with new structures, or adapted to different uses. The survival of the Kintore building, despite being partially damaged and robbed, might be due to the marginal nature of the ground it sits on, which is very boggy in places and contains a large amount of stone, both above and below ground, which inhibited ploughing that might otherwise have removed all traces of the building. Better preserved medieval buildings, such as at Pitcarmick in Perthshire, retain clear divisions between a living end containing a hearth, and byre end with a central drainage slot. No such internal arrangements were apparent at Kintore but soil micromorphology analysis of the soils within the building suggest that there were differences between floor deposits at either end. The west end was associated with domestic activities and the east end was richer in livestock dung, which may indicate the internal division of the house. While there was no central drain within the byre east end of the building, this lay at a lower level than the west end, with the slope aiding drainage if animals were housed there.

Better preserved medieval buildings, such as at Pitcarmick in Perthshire, retain clear divisions between a living end containing a hearth, and byre end with a central drainage slot. No such internal arrangements were apparent at Kintore but soil micromorphology analysis of the soils within the building suggest that there were differences between floor deposits at either end. The west end was associated with domestic activities and the east end was richer in livestock dung, which may indicate the internal division of the house. While there was no central drain within the byre east end of the building, this lay at a lower level than the west end, with the slope aiding drainage if animals were housed there.